Harvey Stein

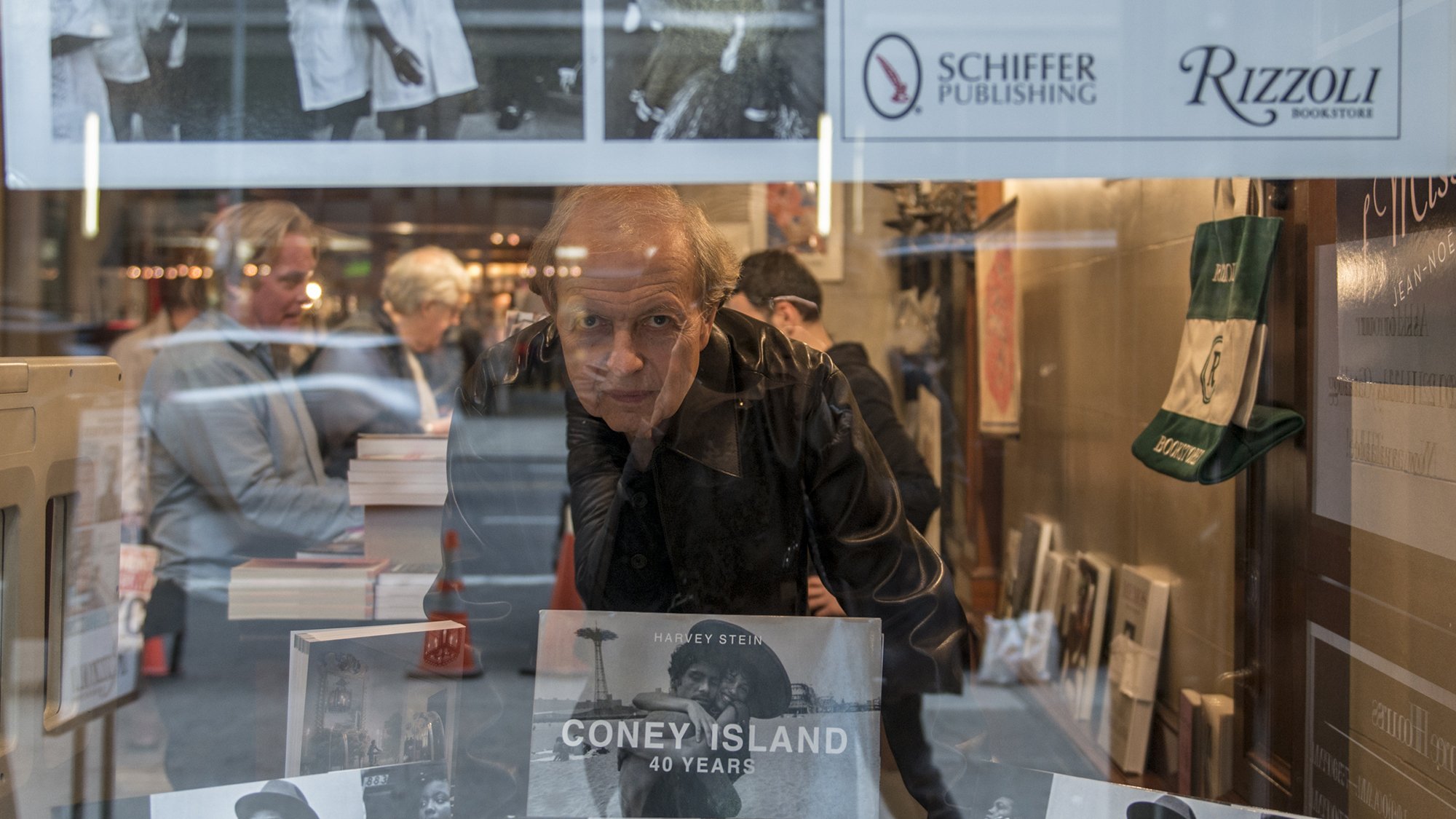

Issue 115 of the NYC Photo Community newsletter features Harvey Stein. Stein is an NYC-based street photographer, educator, lecturer, author, and curator. His photographs have been published in 10 photo books, most recently in 'Coney Island People 50 Years' published by Schiffer Publishing (2022).

Harvey Stein is one of the quintessential photographic chroniclers of New York City, working for more than 50 years to describe the people and feel and streets of our city, from everyday businessmen and women rushing down major avenues of commerce, to off-the-beaten-path spots in NYC’s outer boroughs, to street celebrations all over the city, to a decades-long sustained gaze at our magical summertime getaway Coney Island, where New Yorkers from all over gather to dream, preen, dance, drink, swim, and relax in the sun and sand. Harvey’s view of the city is expansive and intimate - he wants all the details, all the layers, and he wants to be right in the thick of things because that’s the best place to be to allow for people like you and me who weren’t with him to join him in these distinctly NYC experiences. Looking at his work we feel transported to Stein’s side, sharing his pleasure at the great spectacle of New York City.

In Harvey Stein’s photographs, we find ourselves immersed in Stein’s New York City, which for all the joy and good energy he finds, also has plenty of moments of strangeness, grit, grime, and pain. Despite all the complex diversity in this portrayal, Stein’s NYC is also a city that’s logical and believable, and one reason I credit for that is that for much of Stein’s work over all those years, he’s using the same or similar cameras, the same or similar b&w film, and the same open and embracing perspective on the city to make his pictures. It’s a commitment to constancy that I think a lot of young photographers ought to at least consider emulating as they get started in their own long-term approach to subjects and themes. By keeping a fundamental consistency over the years, when it comes time to take a long gaze back, as Stein does in his 10th and latest photo book, Coney Island People 50 Years (Schiffer Publishing, Ltd, 2022), Stein is able to pick work from almost any decade and sequence in pictures that make perfect sense within the larger body of work.

I asked Harvey Stein if he could tell us a little more about his background and approach to photography:

Untitled from the book Briefly Seen New York Street Life (2015) © Harvey Stein

Photography takes me beyond myself yet paradoxically plunges me deeply into myself. It instructs me about the world and about myself. It gives me direction and purpose. It is my shrink, my anti-depressant, and my salvation. It scratches my creative and expressive urges. I truly believe it saved my life. After college, I floundered, with three jobs in eight years, having changed professions several times and spending two of those years in graduate school. I didn’t know which side was up; I was directionless, clueless, may I say lost and bewildered? But once I picked up the camera, I knew there were possibilities and hope. With hard work, and an energy and enthusiasm I hadn’t known before, I became engrossed and totally seduced by the medium and have been happily immersed in it now for over fifty years. I gave up an engineering education and an MBA career with its potential to earn lots of money but have never experienced a moment of regret. I always wanted to be happy, and never thought money would make me that. My happiness comes from my involvement in and commitment to photography and the ability to make images that speak to me and that make me more aware of my fellow man and of myself. In all the years of doing photography, I’ve never lost my focus and love of the medium. Once discovered, I’ve never desired to do any other kind of work. I feel that I carry the medium within me; it’s at the core of my being. I am eternally grateful for that and that I can say I feel fulfilled and satisfied with what I do.

Untitled from the book Briefly Seen New York Street Life (2015) © Harvey Stein

While in college and majoring in metallurgical engineering, I realized that what I really wanted to do was create art. I subsequently became interested in fiction writing, painting and ceramics. After graduation and moving to New York City from Pennsylvania and working in advertising, I eventually realized that while loving the above disciplines, I probably wasn’t “good” enough to pursue a career in any of them. I picked up a camera while stationed in Germany in the U.S. Army. I knew I’d be a photographer someday. While working in the corporate world full time in New York from 1972 to 1979, I photographed during free times and produced my first book, Parallels: A Look at Twins in 1978. Soon afterwards, in 1979, I quit to become a freelance photographer. Photography and New York City were an irresistible combination. I loved being on the streets with the camera, meeting strangers and photographing all kinds of people and public events while exploring most areas of the city.

Untitled from the book Briefly Seen New York Street Life (2015) © Harvey Stein

My subject quickly became the mosaic of the city’s daily life. The people in my work are mostly strangers who I’ve encountered during more than 50 years of photographing in New York City. They are diverse, ordinary people caught up in the turmoil of living, being, moving, and getting along. The images visually portray instants of recognition embodied in a fraction of a second; the ordinary made transcendent. Many tell a story: ambiguous, mysterious, surprising perhaps. I wish to convey a sense of life glimpsed, a sense of contingency and ephemerality.

Untitled from the book Briefly Seen New York Street Life (2015) © Harvey Stein

I believe photographs can speak to us if we are open to them; they are reminders of the past. To look at a family album is to recall vanished memories or to see old friends materialize before our eyes. In making photographs, the photographer is simultaneously a witness to the instant and a recorder of its demise; this is the camera’s power. Photography’s magic is its ability to touch, inspire, sadden, and to connect to each viewer according to that person’s unique sensibility and history. In experiencing these glimpses of New York life, we may in turn become more aware and knowing of our own lives.

Untitled from the book Briefly Seen New York Street Life (2015) © Harvey Stein

For me, photography is a way to learn about life, living and self. Mostly I do long-term projects that are always of personal interest. Photography is the most meaningful thing I could ever do. It is my way of saying, ‘I am here’ and my way of sharing some of my life, experiences and understanding of the world with others.

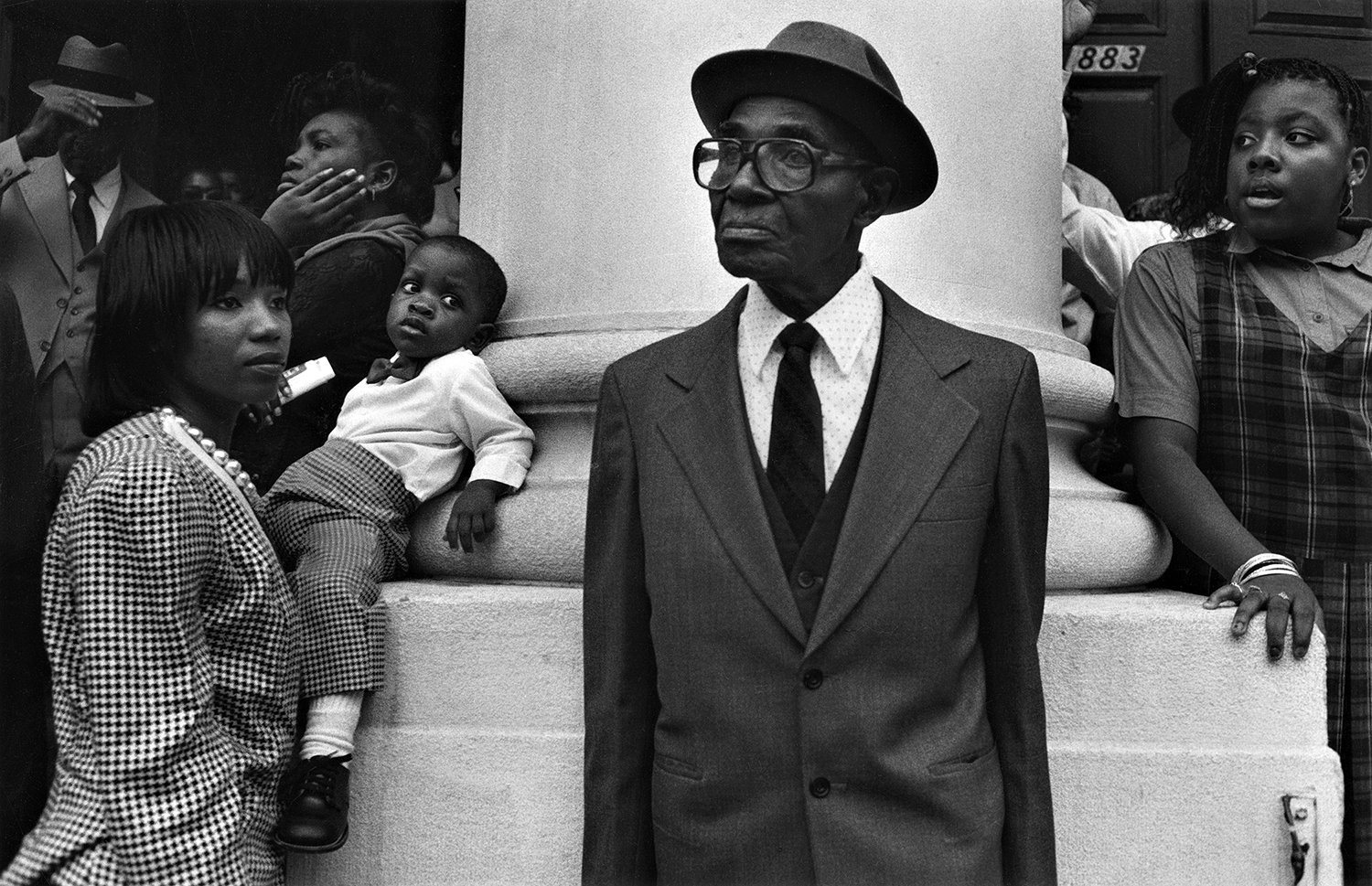

Untitled from the book Harlem Street Portraits (2013) © Harvey Stein

The fact that my focus has not wavered is either a reflection of my consistency or lack of imagination. It has been interesting to me that despite the changes in technology, the same themes and use of black/white film and analog cameras persist in my practice over all these years. I have been intrigued by photographing at Coney Island. My tenth and latest book and third about Coney, Coney Island People 50 Years was just published in September, 2022. Coney Island stays in my mind long after I’ve left, like a movie or song that I can’t seem to get out of my head. The only illusion is the easy life it seems to promise with its eternal sun, sand and ocean. It’s where you bring yourself fully into play rather than being passively manipulated. It’s a place where it’s all up to you, where you can see the world as it really is, and so know yourself as you really are—or ought to be. It has engaged my mind and eye for over a half century. I owe it a great deal. It has endlessly captivated me, tickled my fancy and helped me understand my fellow man, and has made my life richer and fuller.

Untitled from the book Harlem Street Portraits (2013) © Harvey Stein

The advice I would give to would be photographers is to be curious about the world around you and involved in it somehow; to work hard and consistently; to be patient, it all takes time to make successful work and to gain some exposure; to be honest with yourself and your subjects; and to work on long term projects that you can get immersed in and that you return to time and time again. -Harvey Stein September 2022

↡↡↡ More of Harvey Stein’s photography below ↡↡↡

Untitled from the book Harlem Street Portraits (2013) © Harvey Stein

Untitled from the book Harlem Street Portraits (2013) © Harvey Stein

Untitled from the book Harlem Street Portraits (2013) © Harvey Stein

Untitled from the book Coney Island People 50 Years (2022) © Harvey Stein

Untitled from the book Coney Island People 50 Years (2022) © Harvey Stein

Untitled from the book Coney Island People 50 Years (2022) © Harvey Stein

Untitled from the book Coney Island People 50 Years (2022) © Harvey Stein

In addition to Stein’s photography, he’s also a generous and supportive member of the NYC Photo Community in his role as an NYC-based street photographer, educator, lecturer, author, and curator. Stein’s photographs have been published in 10 photo books, most recently in 'Coney Island People 50 Years' published by Schiffer Publishing (2022). Harvey Stein has helped to educate scores of NYC photography students at schools such as SVA, The New School, ICP, and many others. His photos have been published in magazines and newspapers such as The New Yorker, The New York Times, The Guardian, Der Spiegel, and many more. His pictures have also been widely exhibited at museums and galleries, including the George Eastman Museum, the Brooklyn Museum of Art, and ICP, amongst others.

Stein will be teaching an online workshop starting October 25 for the Los Angeles Center of Photography on how to get your photo book published. Interested in signing up? Click here for more information or to register for the class.

For more from Harvey Stein, please check out his website here, or follow him on Instagram here.

Untitled from the book Coney Island People 50 Years (2022) © Harvey Stein

⇣⇣⇣ Next Profile: Sergio Purtell ⇣⇣⇣

Sergio Purtell

Sergio Purtell is a photographer, author of the beautiful Stanley / Barker photo book Love’s Labour, and a master printer whose Brooklyn-based photography printing business Black and White on White has printed work for museums, galleries, and a significant number of notable photographers of our time - people like Robert Adams, Larry Clark, LaToya Ruby Frazier, Jim Goldberg, Mark Steinmetz, and scores more.

Sergio Purtell is a photographer and master printer whose Brooklyn-based photography printing business Black and White on White has printed work for museums, galleries, and a wide range of notable photographers - people like Robert Adams, Larry Clark, LaToya Ruby Frazier, Jim Goldberg, and Mark Steinmetz. Sergio first came onto my radar when I saw him discussing some of the work you’ll see below in a 2015 YouTube video; a conversation between Sergio, MoMA curator Susan Kismaric, and photographer Thomas Roma. While Roma is an old-fashioned Brooklyn character and takes up a lot of oxygen in the video, it was the quieter power and conviction of Purtell’s words and work that ended up staying in my mind. In 2020 Stanley/Barker published Sergio Purtell’s gorgeous photo book Love’s Labour, which collects photos from Sergio’s summer wanderings around Europe in the late 1970s and early-to-mid 1980s; a book worth lingering over as you drift through a Dionysian world seemingly held in permanent dream-like suspension under a sensuous European sun.

Sergio’s work below, from his long-term Real project, is, as the title suggests, far from a dream-like reverie. It’s a very real, absolutely fascinating, multi-layered, deep dive into the visual beauty, spectacle, and splendor of street life in NYC’s outer boroughs. If you go to Sergio’s website, his Real project is presented in five sections, each with scores and scores of photographs. I can’t speak to Queens or the Bronx, but I’ve lived in Brooklyn for more than twenty years, and his project, viewed collectively, is by far the most comprehensive and keenly accurate photographic description of Brooklyn I’ve ever seen both visually and emotionally. These black and white pictures absolutely vacuum up all the strange and overflowing details of the borough and the people and the objects you see and find on the streets and present them back to us in a kind of crystalline, open clarity. This is street photography in encyclopedic and democratic form - nothing is elevated or singled out, it’s just all here for you to explore and wander around at your leisure. Sergio spoke to this point in that 2015 video that first caught my attention in an answer to an audience question about the open-style printing of the image:

I like to think of the prints as being generous…in the way they reveal everything that is going on, and I’m not pointing at anything, in particular, I’m just letting the viewer walk into the pictures and take their pick.

That generosity towards and trust in the viewer is a hallmark of Sergio’s approach as an artist, and it’s an honor to share his work here. I asked Sergio to tell me more about himself and his thoughts about photography:

Van Dam St and Greenpoint Ave, Hunters Point, Queens, NY © Sergio Purtell

I was born in Santiago, Chile, and lived there until 1973, when there was a coup d'etat and the democratically elected socialist president Salvador Allende was killed. Because of the outcome —Chile losing its president and its government — I became highly politicized. I was turning 18 and could become an American citizen by paternity. Understanding that my future would be compromised, I left Chile and moved permanently to the US.

While in Chile, my interest in art started when it seemed like it was the only class I truly enjoyed. I felt with art, I could think on my own, where all other subjects emphasized memorization and zero problem solving. I liked taking things apart to see how they worked and sometimes surprised myself that I could put them back together again. When I got to the US, I started taking classes in art history, figure drawing, graphic design, and architecture, but once I took a class in photography, I quickly realized that was my calling. I love photography’s ability to sustain time and capture its exacting description of life. Even now, every photograph I make is a love poem to photography, one in which I pay homage to life in all its forms.

Center Blvd and 46th Ave, Long Island City, Queens, NY © Sergio Purtell

The one thing I wish I could change about the photography world is less words, better pictures. I am sure this is going to sound harsh to many photographers, especially in the post-modernist world we live in. So much has been said about photography already, to the point where images have lost some of their meaning or importance only to be subdued by words. With the introduction of Instagram and the proliferation of images at such infinite speed, there are few clear voices out there that can cut through the noise and make a difference. One positive change has been to make the medium more inclusive— by artists, educators, curators, galleries, museums, and communities. That gives me hope.

Empty lot somewhere in Bushwick, Brooklyn, NY © Sergio Purtell

I think it would be helpful for artists to disconnect themselves from academic institutions (easy for me to say as I have degrees from RISD and YALE, but I had to pay handsomely even back then). What I mean is that higher education is out of control in terms of cost and outcome, with the percentage of people that end up as academics or working artists is relatively small compared to the amount invested in an artist's career. I would love to see apprenticeship programs or more help from the government — we need more social programs to encourage the arts through mentorship, scholarships, grants, and lower the outrageous ticket price to attend learning institutions. Artists make a huge contribution to society, perhaps not a terribly practical one, but one that gives us hope shows us beauty, and opens our eyes and minds to imagine the impossible and to reaffirm what is possible.

Empty lot somewhere in Bushwick, Brooklyn, NY © Sergio Purtell

If you were to look at my obsessive and extensive website and know anything about the history of photography, you would quickly realize that my love for photography is equally expansive. In some ways, I feel like photography was my destiny — I pay homage to it with what I do every day. I have chosen to help other photographers, and with that choice, I’ve made sacrifices that I am truly willing to make to continue supporting, elevating, and advocating this democratic medium. I am very fortunate to have a great team at the Lab — we are all artists at BWonW and spend our day collaborating with and helping other photographers. It is a pleasure and an inspiration to be around great work and the people who create it.

Atlantic Ave, Ocean Hill, Brooklyn, NY © Sergio Purtell

If I can leave behind one ounce of the legacy that Richard Benson (one of my professors at Yale) so gracefully and generously left behind, I would feel accomplished and that maybe I have passed the baton to the next generation. To other photographers, I would say that as long as you can make pictures, be content. Being in the moment, being compassionate and humble will most likely afford you solid relationships and nourish your artistic life.

Patch of woods in Bushwick, Brooklyn, NY © Sergio Purtell

With this body of work, Real, I was at a place where I thought I had outgrown wanting to photograph the world as it is, searching for beauty and a place where light and landscape meet. So I began to re-create a world in which I could take the kind of photographs I wanted to make. I tried reconstructing the parts of the world that had been discarded, abandoned, or thrown away. Ultimately I was looking for some idea of real and beauty rooted in the world we find ourselves in now.

Richmond St and Dinsmore Place, Cypress Hills, Brooklyn, NY © Sergio Purtell

I have always printed in a very open style, which was definitely influenced by my time at Yale. I remember that Richard Benson gave me a piece of material used in offset printing— the equivalent of a double 00 filter — that I would use to flash the print as a final touch to fill in any potential too-bright highlight. Also, I would split filter my prints. I can tell you that all this was incredibly tedious and time-consuming, but in the end, it would yield these beautifully open prints, with every possible midtown and a touch of black in the shadow areas and compressed highlights.

Gowanus Canal and 3rd St, Gowanus, Brooklyn, NY © Sergio Purtell

My book Love’s Labour came out in 2020, and I have been ruminating about publishing a second book — although keeping a business (BWonW.com) running during COVID has taken up most of my time and energy. For now, I post on Instagram (although I don’t post new photos as much as I should) and have an extensive website for those interested in looking.

Lee Ave and Flushing Ave, South Williamsburg, Brooklyn, NY © Sergio Purtell

Lincoln Ave and 138th St, Bronx, NY © Sergio Purtell

All photographs were made ranging from 2008 to 2014 © Sergio Purtell

Sergio Purtell - Edward Mapplethorpe, 2020 (Color portrait at top of post)

You can see a plentitude of more photos by Sergio on his website here: sergiopurtell.com His book published by Stanley/Barker, Love’s Labour is currently sold out. You can follow Sergio on Instagram here: @sergio_purtell

⇣⇣⇣ Next Profile: Ryan Frigillana ⇣⇣⇣

Ryan Frigillana

Ryan Frigillana’s work reveals a rich sensitivity to nature and intimate and incisive explorations of family, migration, and identity.

I first came across Ryan Frigillana’s work this past spring when one of his images of the Orchid Show at the New York Botanical Garden was published as the ‘Go opener’ in the New Yorker magazine. It was a dazzling photo of mirrors and orchids that showed me the beauty of nature - of flowers - presented in a new, fresh way, as were the outtakes he shared on his Instagram. Looking up Ryan’s website and Instagram, I was rewarded with more photos showing his rich sensitivity to nature along with intimate and incisive explorations of family, migration, and identity. The connections between family and nature are often explicit in his work and made me consider the idea of family as ecosystem - and what it can mean to move people born or raised in one environment to another. While we can all thrive in a new environment, the initial months and years of displacement can often prove difficult. When we have at last made a flourishing life in a new place, where does that thing inside us go that still misses the soil where roots first grew?

Broken Tractor, 2022. From the series, Manong. © Ryan Frigillana

I asked Ryan to tell me about his path into photography and the visual arts:

I was born in the Philippines and immigrated to the States with my family when I was about three years old. I don't come from an art background. I was groomed to have a career in healthcare from a young age, but I had little interest in the sciences, and I was terrible with math. Because of the language barrier growing up, I had difficulty making friends, so I took to sketching, and making comics, and writing poetry. Pablo Neruda was a monumental figure for me; his writing and way of visualizing the common world played a huge role in how I developed my sensibilities early on. I have always been an expressive person, but I never considered photography an artform until I was much older; the camera only served a utilitarian purpose in my household for memorializing moments and milestones. I took an Intro to Photography elective while I was in nursing school, and that was my first real taste of it outside of that context.

Reflection, 2022. From the series, Manong. © Ryan Frigillana

My interest in the medium blossomed when I bought my first camera (a Nikon FE) and taught myself how to process B&W film at home. At this point, I had dropped out of nursing school and started working a job in horticulture, which I did for several years. In the meantime, I learned to develop my eye by photographing my family, and by devouring photobooks and films (Stanley Kubrick, Terrence Malick, and Wong Kar-wai were huge influences). Oddly enough it was during this day job in horticulture, where I found myself staring at plants all day, that I learned to truly pay attention to my surroundings, to recognize the fragility and wonder in the smallest things—in shapes and curves, and in the movement of light and shadow. That job taught me how to be present with myself, to slow down and appreciate stillness. I began to observe the expressive gestures of plants—in the ways they would droop, or arch upwards in the sun, or how they would dry, wither, and transform. Training myself to find intimacy in the inanimate translated into how I observed and photographed people. Those years were formative for me in developing my visual sensibilities, but I still needed to develop a vocabulary of skills and critical thinking to match. After a long hiatus, I decided to enroll myself back into school to study photography full time.

Starved, 2020. From the series, The Weight of Slumber. © Ryan Frigillana

I joke that I became a photographer because I'm too impatient to draw or paint. There is some truth to that. What I love about photography is its immediacy and ubiquity. Anyone can make a photograph quickly and easily, but to create images with intent and to construct meaning out of an already-hyper-visual world is a challenge that I relish. My excitement for the medium lies in its slipperiness and its serial nature, and the potential that can be born from all that—that's what keeps me coming back to it. Images are everywhere, but you can't really pin them down because our relationships to them change over time and place. They are like little seeds that contain a dormant life. Where that seed is planted, contextually, will determine what meaning I am able to harvest from it later. I have many images collected in my archive that I like, but they don't yet have a "home" so to speak.

Direction Home, 2020. From the series, The Weight of Slumber. © Ryan Frigillana

When it comes to my praxis, I am at the point where I've found the itch that will take me a lifetime to scratch. I'm deeply invested in using photography to process my identity as a Filipino-American and employing this language as a catalyst for dialogue—to build community, connection, and understanding. My mother used to photograph our family as her way to celebrate and remember ourselves; I hope that what I’m doing with a camera today honors that spirit and much more. I am currently working on my next long-term project titled "Manong" that engages with the overlooked history of Filipino migrant workers in the U.S., using my own family to explore themes of generational labor and faith. I aim to publish this work as a book in the distant future.

Father, 2021 / A Heaven We Share (diptych), 2022. From the series, Manong. © Ryan Frigillana

My relationship to photography is one that’s in constant flux, but it is through these changes that I grow and deepen my connection to it. I've gone through many phases of interest in my work, from street, to still life, to documentary and conceptual work, etc. — but it’s all vocabulary building, and all ongoing. In the end, these experiences only serve to strengthen my relationship to my craft and help me better understand my position within it. Your ability to create is one thing no one can ever take away from you, so why not try everything? Throw yourself into your practice—suck at it, exceed, and suck at it some more. Keep working until you find yourself saying what you really want to say, not what others want to hear. But to arrive at that point, you just need to keep making. Half of the time, I don't know what I'm doing; I never have it all figured out. But I allow the act of creating to guide my steps. I can have all the greatest ideas in the world, but I need to try them to see where they lead me next. When I’ve done far more failing than succeeding, then I think maybe I’m on to something worthwhile...hopefully. But regardless of process, I am reminded to always begin from a place of genuine curiosity—a place that is authentic to me.

Knowing Good and Evil, 2018. From the series, Visions of Eden. © Ryan Frigillana

The House They Built, 2022. From the series, Balikbayan. © Ryan Frigillana

Protector, Predator, 2021. From the series, Manong. © Ryan Frigillana

False Idols, 2020. From the series, Visions of Eden. © Ryan Frigillana

Family Tree, Emme’s Painting (White Picket Fence), 2022. From the series, Manong. © Ryan Frigillana

Ryan Frigillana (he/him), b. Iligan City, Philippines, is a New York-based visual artist working with photography and image archives. His work reflects on the construction of familial identity, history, and home as a first-generation American.

He is the author of two monographs: Visions of Eden (self-published, 2020) and The Weight of Slumber (Penumbra Foundation, 2021). Select awards include a MUUS Collection / Penumbra Foundation Risograph Print & Publication Residency, the NYFA / JGS Fellowship for Photography, and being selected for the 2022 NY Times Portfolio Review.

He is open for projects and commissions.

⇣⇣⇣ Next Profile: Christian Michael Filardo ⇣⇣⇣

Jesse Warner

Jesse Warner is a New York City-based photographer who makes fun and funny and sexy portraits of people and food that are absolutely delightful.

While I’ve long been impressed by professional food photographers’ abilities to style and photograph food in a way that makes food look beautiful and special and precious, those photos most often reflect a marketing mindset and relationship to food that I just don’t have. I moved to NYC to eat food not sell it. I like to get messy with food. I like having fun with food. My mindset towards food is I once bought a domain called mouthcooking.com because I was so sure that would be the next food trend…recipes where you get different ingredients and combine them in your mouth to make the finished dishes. (Take one bite of banana. Hold in mouth. Take one bite of dark chocolate bar. Chew freely.) If anyone could make my messy stupid idea into an actual new trend, it would be Jesse Warner. His photos of people and food are so fun and funny and sexy and delightful that there’s only one word that can sum up how I feel about his work…DELICIOUS. I asked Jesse to tell me more about his path in photography:

Drunk Pizza Lust, Brooklyn, NYC. © Jesse Warner

I thought I wanted to be a chef or photojournalist, and I guess I ended up somewhere in between. When I moved to this city, I took a job at a café in Long Island City that prides itself on being a community space that actually pays minimum wage(anything over 30 hours is cash!) with an abusive boss. I had only enough money for a one month sublet in Astoria in a freezing February and had no money for the subway and would buy off-brand poptarts from the dollar store and give one to the homeless man at the R train. My uncle was a sportscaster for a radio station and found out that I was interested in photography and gave me his old Canon Rebel G and some expired film to start. Since I had no friends, I started interviewing random people on the street that looked interesting and set up photoshoots with some truly odd-ball craigslist ads. For some reason, I found comfort in Flushing, Queens and would frequently go there and take street portraits and eat at New World Mall. Most of my work aims to express how food is a reason for people to come together. My early photography was me exploring a city new to me, and pinging the world to say "I exist".

I've worked with and have been attracted to food my whole life. My parents did not know how to cook, so I had to teach myself. I would watch Iron Chef Japan religiously and would make gigantic messes in the kitchen trying to recreate dishes in pursuit of flavor. I thought I hated food for the longest time. I grew up eating things like 98% fat free burgers with no salt or pepper, on a George Forman grill with raw onion, raw mushroom, lettuce, and thick cut off-season tomato rare on a soggy sesame seed bun. I started working in kitchens after discovering that eating out or making my own food was the key to a life worth living. I started as a deli boy and somehow years later worked three years at a Michelin Starred restaurant here in NYC as a Kitchen Lead. During the pandemic, I focused more on my photography while also working at the farmers market and various catering companies. I like to keep my schedule fairly flexible to avoid the nine-to-five burnout which is very important to me.

My One Desire, Brooklyn, NYC. © Jesse Warner

One of the most parallel shoots references from cooking to film was climbing a ladder to get ingredients and measure them out on a scale and climb back up. To save time, I somehow mastered pouring oils, vinegars and all sorts of liquids from the top of the ladder into a tiny 6 pan and be able to accurately measure something out for a recipe. Chef would be pissed, but have nothing to say after I explained how much time I was saving and how I made zero mess. This inspired my shoots where I had a model pour oil and vinegar mid-air and captured it. I loved the way the flash captures liquids on film. The plate is a canvas. You have all sorts of out of these highly saturated right out of the box colors swirling around the plate and you want to make it look pretty. That's why I use Ultramax 400

Don't Cross the Streams, Brooklyn, NYC. © Jesse Warner

My breakthrough moment that food would be a recurring theme in my portraits is when I made a mess at work and the head chef came over to make a big scene. I jokingly said "I'm an artist, I was just trying to paint with colors". I went on to say that I should make a Youtube channel where I leave the top off blenders in a white room and how there's definitely an audience. Somehow he didn't murder me, but in that moment everything came together and nothing he said could have made me feel anything other than pure joy. Here I am making these pretty little sauces and these pretty little plates and all I want to do is make messes. My work is me saying "so what?" to everyone who has ever called me "Messy Jesse" since kindergarten, because at the end of the day, I'm having a blast.

Ramen Noodle Bath, Brooklyn, NYC. © Jesse Warner

The most exciting photo books to me are honestly old family photo albums including my own. My family is especially goofy and I'll constantly be chasing the candidness of being a colorful dressed kid in the 90's that does what he wants. My grandmother has an especially large collection of photo prints of people that is going to be a massive archive project sometime in the future. I think family photos, particularly on trips, provide that intimacy and comfort that allows you to be a true loose version of yourself and that's what makes a great photo.

Ronnybrook Romance, Brooklyn, NYC. © Jesse Warner

You can buy stickers, t-shirts, and postcards with Jesse Warner’s photos on them at his online store here.

Follow Jesse on Instagram: @warnerjesse Keep an eye out for Jesse’s new website, coming soon here.

Portrait of Jesse Warner at top of post: © Shandy Tsai (@shandytsart)

⇣⇣⇣ Next Profile: Tracy Dong ⇣⇣⇣

Tracy Dong

Tracy Dong is a Vancouver-born, Brooklyn-based photographer and visual artist whose work aims to represent the under-represented, describe the relationship between individuals and their surroundings, and reveal the extraordinary opera underlying seemingly ordinary life. In a complex and chaotic world, she finds her pictures in moments of simple emotional and intimate connection with her subjects.

Exploring Tracy Dong’s photography I find a gentle lyricism that I respond to - many moments she holds for us in her pictures are quiet, intimate, and tender. The world she is describing is closely observed but seemingly rarely disturbed by her picture-making, even when her subject, like Edward in the photo Edward Zhu for Future Blues Vintage gazes directly at her camera, and the image is staged. It all just seems like the world just as it was when she found it. Her focus is not only on quiet moments of connection - I also appreciate when she engages with the festive and wild life of the world - like her short super 8 film at the end of this feature that captures the fun and joy of NYC’s Pride celebration. Like her photos, her film puts me right at the emotional center of the moment(s).

Revival of NYC, Pride Weekend, New York City, 2021 © Tracy Dong

I asked Tracy to tell us a little about her journey in photography:

I am the daughter of a war veteran, so a lot of my father’s photos were erased to protect my family’s identity and refugee status. Most of my childhood was spent re-creating the family archival, and I was always around something with lenses, picking up on the skill as I dabbled in and out of the arena of photography throughout my life. I shot video shorts of myself at my childhood home when I was 7 or 8, created photo albums when I traveled for tennis as a teenager, tried out modeling when I was in college but was told to slim down if I wanted to continue. That experience inherently gave me the impulse that I was going to create my own photographs and I didn’t need anyone to tell me who to put in them or how to create them. I started buying film cameras and taking photos with friends for fun, but gave up before grad school was over as I saw no return on investment on film at the time and felt defeated by the emergence of “iPhone photography”. Like many recently self-proclaimed photographers, the pandemic was what made me pick it up again. It was and still is a period of me trying to process the imminent shifts going on around me, and what it was doing to my mental health. Instinctively I bought an army of cameras. It became a way to channel the emotions. I guess like what the 1968 gunshot to Warhol did for the Warhol Diaries, I just began shooting incessantly to document everything and understand what I was going through.

The act of photographing is almost like my own act of self-reconciliation. Growing up in an immigrant family, I was taught to not trust anyone and keep to myself. I think throughout my life, I missed out on understanding the importance of nurturing connection, tenderness, and human fragility. Now, these are some of the themes present in my photographs because I am, in a way, catching up with myself. Capturing the delicate aura of another person’s constructed life in front of me, or upholding communities who normally feel invisible feel beautifully visible. This has become my way to access my heart and allow myself to connect with others. Once the technicality is out of the way, to me the art comes into play when you let your higher consciousness draw you towards the subject you want to photograph and tell you what it means to you when get the photo back. It’s a completely meditative and spiritual experience to delve into and share that level of intimacy, to see another, or others, as they are fully. We forget the sacredness in being able to see, listen, and share – our hearts, our stories. Shooting on film just so happens to heighten this meditative experience with how slow and meticulous each step is, and to achieve the tenderness theme I am after. I don’t think there’s anything more satisfying than nailing the rich and decadent texture, color, and light that films brings to a photograph, while it tells a compelling story.

I get inspiration from anything – the way 6PM evening light cloaks my bedroom, heartbreak, watching my friends fall in love, a lesson I learned in therapy, an Ingmar Bergman film, a Townes Van Zandt melody. They all ignite a feeling I want to bottle and immortalize into a photograph. I seek to create an unflinching portrait the way Joan Didion executes a sentence, and chase beauty in unlikely places through street photography the way Anthony Bourdain seeks the perfect meal in third-world countries. When I’m not shooting or working my day job, I’m gathering inspiration and mentally framing potential photos, so in a way I’m never not working. I guess that is the inquisitive freedom and curse of being a photographer.

I recently started to incorporate writing into my photography, which can be risky but can add so much depth to its meaning. A photo can have endless interpretations, but the addition of writing can corner the photo into a box. Not only am I presenting a visual, but I am verbally coercing the viewer how to interpret it. There are certain projects where that makes sense, such as the photo essay I did on my father that had a deep back-story to it that only text can serve the viewer to understand. The other in which I am currently working on documents street life in recent countries I’ve traveled to. This series will be presented in photographs alone, as it is about the visceral elements of these places and feeling the rhythm and flow of daily life through its images.

Follow Tracy Dong on Instagram: @tracytdong Film Instagram: @feelingson35mm and see more of her work on her website, tracytdong.com

Photo at top of post: Self Portrait, 2020. © Tracy Dong

↓ ↓ ↓ All Photos and video in this post © Tracy Dong↓ ↓ ↓

Father Playing the Piano at Home, Vancouver, Canada, 2021 © Tracy Dong

Edward Zhu for Future Blues Vintage, San Francisco, California, 2021 © Tracy Dong

Sunset over Niagara Falls, Buffalo, New York, 2021 © Tracy Dong

Ferry to Rockaway Beach, New York, 2021 © Tracy Dong

A short film celebrating Pride 2021 in New York City © Tracy Dong

Tracy Dong is a Vancouver-born, Brooklyn-based photographer and visual artist whose work aims to represent the under-represented, describe the relationship between individuals and their surroundings, and reveal the extraordinary opera underlying seemingly ordinary life. In a complex and chaotic world, she finds her pictures in moments of simple emotional and intimate connection with her subjects.

Website: tracytdong.com Instagram: @tracytdong Film Instagram: @feelingson35mm