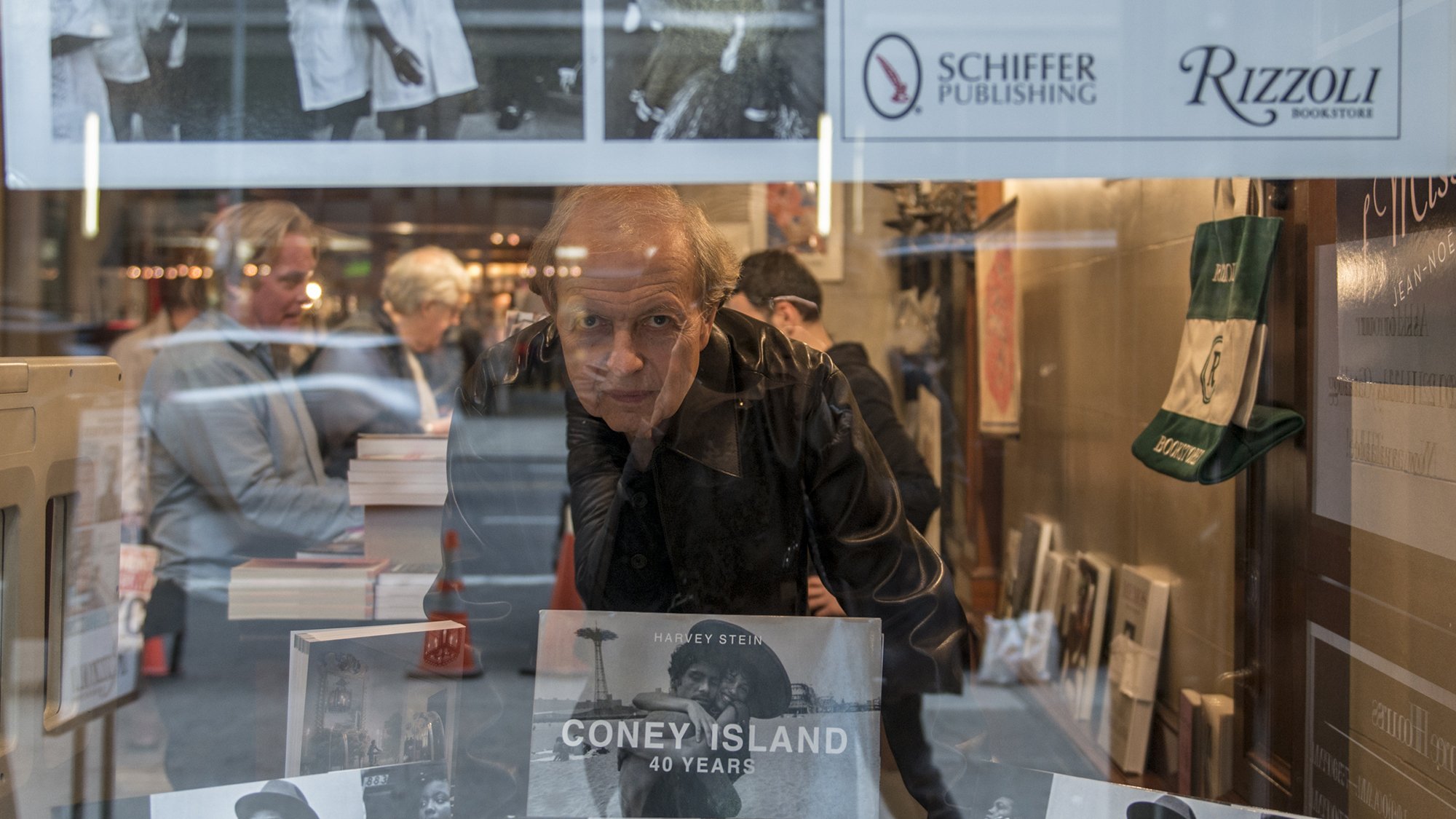

Harvey Stein

Issue 115 of the NYC Photo Community newsletter features Harvey Stein. Stein is an NYC-based street photographer, educator, lecturer, author, and curator. His photographs have been published in 10 photo books, most recently in 'Coney Island People 50 Years' published by Schiffer Publishing (2022).

Harvey Stein is one of the quintessential photographic chroniclers of New York City, working for more than 50 years to describe the people and feel and streets of our city, from everyday businessmen and women rushing down major avenues of commerce, to off-the-beaten-path spots in NYC’s outer boroughs, to street celebrations all over the city, to a decades-long sustained gaze at our magical summertime getaway Coney Island, where New Yorkers from all over gather to dream, preen, dance, drink, swim, and relax in the sun and sand. Harvey’s view of the city is expansive and intimate - he wants all the details, all the layers, and he wants to be right in the thick of things because that’s the best place to be to allow for people like you and me who weren’t with him to join him in these distinctly NYC experiences. Looking at his work we feel transported to Stein’s side, sharing his pleasure at the great spectacle of New York City.

In Harvey Stein’s photographs, we find ourselves immersed in Stein’s New York City, which for all the joy and good energy he finds, also has plenty of moments of strangeness, grit, grime, and pain. Despite all the complex diversity in this portrayal, Stein’s NYC is also a city that’s logical and believable, and one reason I credit for that is that for much of Stein’s work over all those years, he’s using the same or similar cameras, the same or similar b&w film, and the same open and embracing perspective on the city to make his pictures. It’s a commitment to constancy that I think a lot of young photographers ought to at least consider emulating as they get started in their own long-term approach to subjects and themes. By keeping a fundamental consistency over the years, when it comes time to take a long gaze back, as Stein does in his 10th and latest photo book, Coney Island People 50 Years (Schiffer Publishing, Ltd, 2022), Stein is able to pick work from almost any decade and sequence in pictures that make perfect sense within the larger body of work.

I asked Harvey Stein if he could tell us a little more about his background and approach to photography:

Untitled from the book Briefly Seen New York Street Life (2015) © Harvey Stein

Photography takes me beyond myself yet paradoxically plunges me deeply into myself. It instructs me about the world and about myself. It gives me direction and purpose. It is my shrink, my anti-depressant, and my salvation. It scratches my creative and expressive urges. I truly believe it saved my life. After college, I floundered, with three jobs in eight years, having changed professions several times and spending two of those years in graduate school. I didn’t know which side was up; I was directionless, clueless, may I say lost and bewildered? But once I picked up the camera, I knew there were possibilities and hope. With hard work, and an energy and enthusiasm I hadn’t known before, I became engrossed and totally seduced by the medium and have been happily immersed in it now for over fifty years. I gave up an engineering education and an MBA career with its potential to earn lots of money but have never experienced a moment of regret. I always wanted to be happy, and never thought money would make me that. My happiness comes from my involvement in and commitment to photography and the ability to make images that speak to me and that make me more aware of my fellow man and of myself. In all the years of doing photography, I’ve never lost my focus and love of the medium. Once discovered, I’ve never desired to do any other kind of work. I feel that I carry the medium within me; it’s at the core of my being. I am eternally grateful for that and that I can say I feel fulfilled and satisfied with what I do.

Untitled from the book Briefly Seen New York Street Life (2015) © Harvey Stein

While in college and majoring in metallurgical engineering, I realized that what I really wanted to do was create art. I subsequently became interested in fiction writing, painting and ceramics. After graduation and moving to New York City from Pennsylvania and working in advertising, I eventually realized that while loving the above disciplines, I probably wasn’t “good” enough to pursue a career in any of them. I picked up a camera while stationed in Germany in the U.S. Army. I knew I’d be a photographer someday. While working in the corporate world full time in New York from 1972 to 1979, I photographed during free times and produced my first book, Parallels: A Look at Twins in 1978. Soon afterwards, in 1979, I quit to become a freelance photographer. Photography and New York City were an irresistible combination. I loved being on the streets with the camera, meeting strangers and photographing all kinds of people and public events while exploring most areas of the city.

Untitled from the book Briefly Seen New York Street Life (2015) © Harvey Stein

My subject quickly became the mosaic of the city’s daily life. The people in my work are mostly strangers who I’ve encountered during more than 50 years of photographing in New York City. They are diverse, ordinary people caught up in the turmoil of living, being, moving, and getting along. The images visually portray instants of recognition embodied in a fraction of a second; the ordinary made transcendent. Many tell a story: ambiguous, mysterious, surprising perhaps. I wish to convey a sense of life glimpsed, a sense of contingency and ephemerality.

Untitled from the book Briefly Seen New York Street Life (2015) © Harvey Stein

I believe photographs can speak to us if we are open to them; they are reminders of the past. To look at a family album is to recall vanished memories or to see old friends materialize before our eyes. In making photographs, the photographer is simultaneously a witness to the instant and a recorder of its demise; this is the camera’s power. Photography’s magic is its ability to touch, inspire, sadden, and to connect to each viewer according to that person’s unique sensibility and history. In experiencing these glimpses of New York life, we may in turn become more aware and knowing of our own lives.

Untitled from the book Briefly Seen New York Street Life (2015) © Harvey Stein

For me, photography is a way to learn about life, living and self. Mostly I do long-term projects that are always of personal interest. Photography is the most meaningful thing I could ever do. It is my way of saying, ‘I am here’ and my way of sharing some of my life, experiences and understanding of the world with others.

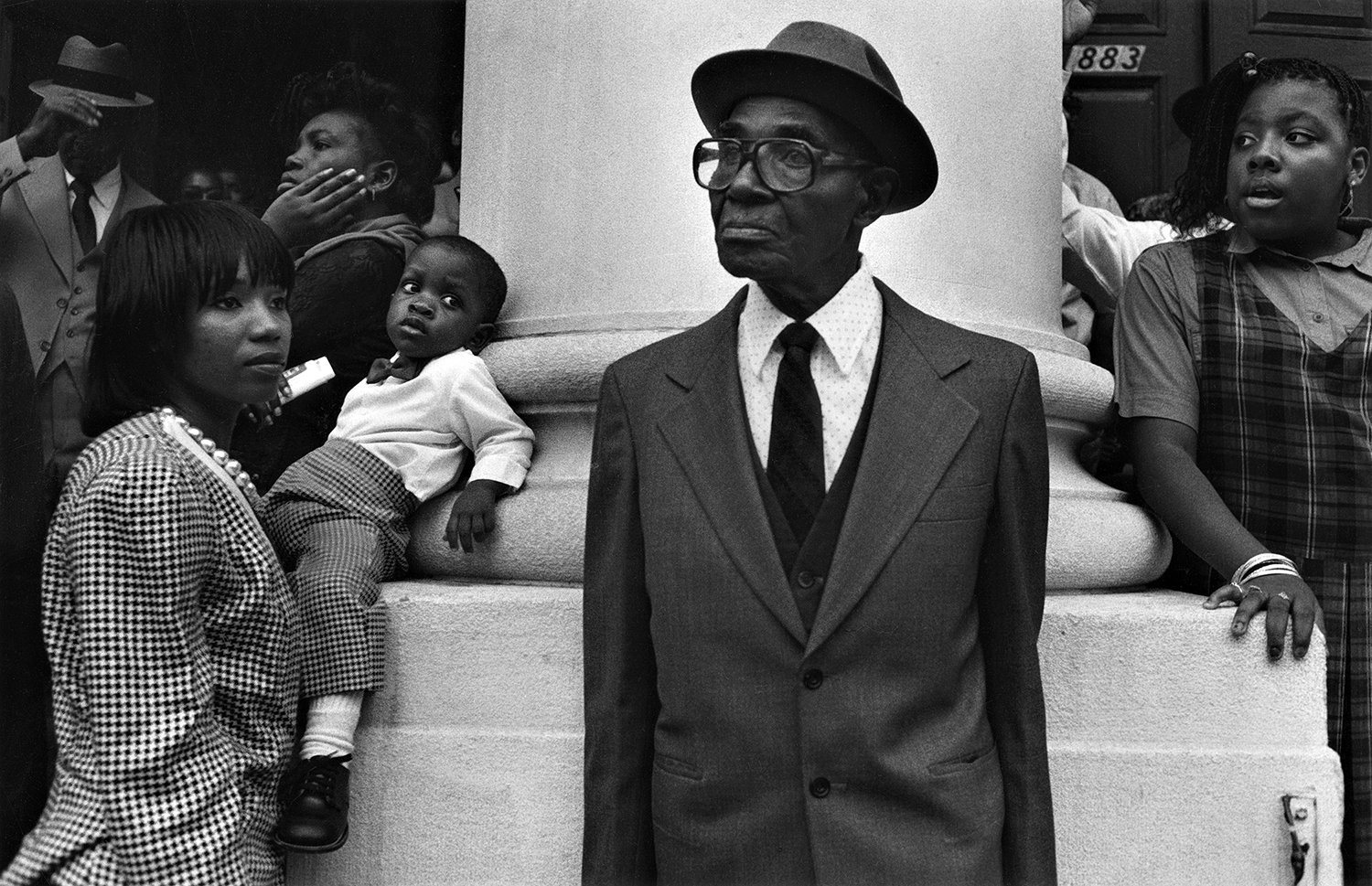

Untitled from the book Harlem Street Portraits (2013) © Harvey Stein

The fact that my focus has not wavered is either a reflection of my consistency or lack of imagination. It has been interesting to me that despite the changes in technology, the same themes and use of black/white film and analog cameras persist in my practice over all these years. I have been intrigued by photographing at Coney Island. My tenth and latest book and third about Coney, Coney Island People 50 Years was just published in September, 2022. Coney Island stays in my mind long after I’ve left, like a movie or song that I can’t seem to get out of my head. The only illusion is the easy life it seems to promise with its eternal sun, sand and ocean. It’s where you bring yourself fully into play rather than being passively manipulated. It’s a place where it’s all up to you, where you can see the world as it really is, and so know yourself as you really are—or ought to be. It has engaged my mind and eye for over a half century. I owe it a great deal. It has endlessly captivated me, tickled my fancy and helped me understand my fellow man, and has made my life richer and fuller.

Untitled from the book Harlem Street Portraits (2013) © Harvey Stein

The advice I would give to would be photographers is to be curious about the world around you and involved in it somehow; to work hard and consistently; to be patient, it all takes time to make successful work and to gain some exposure; to be honest with yourself and your subjects; and to work on long term projects that you can get immersed in and that you return to time and time again. -Harvey Stein September 2022

↡↡↡ More of Harvey Stein’s photography below ↡↡↡

Untitled from the book Harlem Street Portraits (2013) © Harvey Stein

Untitled from the book Harlem Street Portraits (2013) © Harvey Stein

Untitled from the book Harlem Street Portraits (2013) © Harvey Stein

Untitled from the book Coney Island People 50 Years (2022) © Harvey Stein

Untitled from the book Coney Island People 50 Years (2022) © Harvey Stein

Untitled from the book Coney Island People 50 Years (2022) © Harvey Stein

Untitled from the book Coney Island People 50 Years (2022) © Harvey Stein

In addition to Stein’s photography, he’s also a generous and supportive member of the NYC Photo Community in his role as an NYC-based street photographer, educator, lecturer, author, and curator. Stein’s photographs have been published in 10 photo books, most recently in 'Coney Island People 50 Years' published by Schiffer Publishing (2022). Harvey Stein has helped to educate scores of NYC photography students at schools such as SVA, The New School, ICP, and many others. His photos have been published in magazines and newspapers such as The New Yorker, The New York Times, The Guardian, Der Spiegel, and many more. His pictures have also been widely exhibited at museums and galleries, including the George Eastman Museum, the Brooklyn Museum of Art, and ICP, amongst others.

Stein will be teaching an online workshop starting October 25 for the Los Angeles Center of Photography on how to get your photo book published. Interested in signing up? Click here for more information or to register for the class.

For more from Harvey Stein, please check out his website here, or follow him on Instagram here.

Untitled from the book Coney Island People 50 Years (2022) © Harvey Stein

⇣⇣⇣ Next Profile: Sergio Purtell ⇣⇣⇣

Sergio Purtell

Sergio Purtell is a photographer, author of the beautiful Stanley / Barker photo book Love’s Labour, and a master printer whose Brooklyn-based photography printing business Black and White on White has printed work for museums, galleries, and a significant number of notable photographers of our time - people like Robert Adams, Larry Clark, LaToya Ruby Frazier, Jim Goldberg, Mark Steinmetz, and scores more.

Sergio Purtell is a photographer and master printer whose Brooklyn-based photography printing business Black and White on White has printed work for museums, galleries, and a wide range of notable photographers - people like Robert Adams, Larry Clark, LaToya Ruby Frazier, Jim Goldberg, and Mark Steinmetz. Sergio first came onto my radar when I saw him discussing some of the work you’ll see below in a 2015 YouTube video; a conversation between Sergio, MoMA curator Susan Kismaric, and photographer Thomas Roma. While Roma is an old-fashioned Brooklyn character and takes up a lot of oxygen in the video, it was the quieter power and conviction of Purtell’s words and work that ended up staying in my mind. In 2020 Stanley/Barker published Sergio Purtell’s gorgeous photo book Love’s Labour, which collects photos from Sergio’s summer wanderings around Europe in the late 1970s and early-to-mid 1980s; a book worth lingering over as you drift through a Dionysian world seemingly held in permanent dream-like suspension under a sensuous European sun.

Sergio’s work below, from his long-term Real project, is, as the title suggests, far from a dream-like reverie. It’s a very real, absolutely fascinating, multi-layered, deep dive into the visual beauty, spectacle, and splendor of street life in NYC’s outer boroughs. If you go to Sergio’s website, his Real project is presented in five sections, each with scores and scores of photographs. I can’t speak to Queens or the Bronx, but I’ve lived in Brooklyn for more than twenty years, and his project, viewed collectively, is by far the most comprehensive and keenly accurate photographic description of Brooklyn I’ve ever seen both visually and emotionally. These black and white pictures absolutely vacuum up all the strange and overflowing details of the borough and the people and the objects you see and find on the streets and present them back to us in a kind of crystalline, open clarity. This is street photography in encyclopedic and democratic form - nothing is elevated or singled out, it’s just all here for you to explore and wander around at your leisure. Sergio spoke to this point in that 2015 video that first caught my attention in an answer to an audience question about the open-style printing of the image:

I like to think of the prints as being generous…in the way they reveal everything that is going on, and I’m not pointing at anything, in particular, I’m just letting the viewer walk into the pictures and take their pick.

That generosity towards and trust in the viewer is a hallmark of Sergio’s approach as an artist, and it’s an honor to share his work here. I asked Sergio to tell me more about himself and his thoughts about photography:

Van Dam St and Greenpoint Ave, Hunters Point, Queens, NY © Sergio Purtell

I was born in Santiago, Chile, and lived there until 1973, when there was a coup d'etat and the democratically elected socialist president Salvador Allende was killed. Because of the outcome —Chile losing its president and its government — I became highly politicized. I was turning 18 and could become an American citizen by paternity. Understanding that my future would be compromised, I left Chile and moved permanently to the US.

While in Chile, my interest in art started when it seemed like it was the only class I truly enjoyed. I felt with art, I could think on my own, where all other subjects emphasized memorization and zero problem solving. I liked taking things apart to see how they worked and sometimes surprised myself that I could put them back together again. When I got to the US, I started taking classes in art history, figure drawing, graphic design, and architecture, but once I took a class in photography, I quickly realized that was my calling. I love photography’s ability to sustain time and capture its exacting description of life. Even now, every photograph I make is a love poem to photography, one in which I pay homage to life in all its forms.

Center Blvd and 46th Ave, Long Island City, Queens, NY © Sergio Purtell

The one thing I wish I could change about the photography world is less words, better pictures. I am sure this is going to sound harsh to many photographers, especially in the post-modernist world we live in. So much has been said about photography already, to the point where images have lost some of their meaning or importance only to be subdued by words. With the introduction of Instagram and the proliferation of images at such infinite speed, there are few clear voices out there that can cut through the noise and make a difference. One positive change has been to make the medium more inclusive— by artists, educators, curators, galleries, museums, and communities. That gives me hope.

Empty lot somewhere in Bushwick, Brooklyn, NY © Sergio Purtell

I think it would be helpful for artists to disconnect themselves from academic institutions (easy for me to say as I have degrees from RISD and YALE, but I had to pay handsomely even back then). What I mean is that higher education is out of control in terms of cost and outcome, with the percentage of people that end up as academics or working artists is relatively small compared to the amount invested in an artist's career. I would love to see apprenticeship programs or more help from the government — we need more social programs to encourage the arts through mentorship, scholarships, grants, and lower the outrageous ticket price to attend learning institutions. Artists make a huge contribution to society, perhaps not a terribly practical one, but one that gives us hope shows us beauty, and opens our eyes and minds to imagine the impossible and to reaffirm what is possible.

Empty lot somewhere in Bushwick, Brooklyn, NY © Sergio Purtell

If you were to look at my obsessive and extensive website and know anything about the history of photography, you would quickly realize that my love for photography is equally expansive. In some ways, I feel like photography was my destiny — I pay homage to it with what I do every day. I have chosen to help other photographers, and with that choice, I’ve made sacrifices that I am truly willing to make to continue supporting, elevating, and advocating this democratic medium. I am very fortunate to have a great team at the Lab — we are all artists at BWonW and spend our day collaborating with and helping other photographers. It is a pleasure and an inspiration to be around great work and the people who create it.

Atlantic Ave, Ocean Hill, Brooklyn, NY © Sergio Purtell

If I can leave behind one ounce of the legacy that Richard Benson (one of my professors at Yale) so gracefully and generously left behind, I would feel accomplished and that maybe I have passed the baton to the next generation. To other photographers, I would say that as long as you can make pictures, be content. Being in the moment, being compassionate and humble will most likely afford you solid relationships and nourish your artistic life.

Patch of woods in Bushwick, Brooklyn, NY © Sergio Purtell

With this body of work, Real, I was at a place where I thought I had outgrown wanting to photograph the world as it is, searching for beauty and a place where light and landscape meet. So I began to re-create a world in which I could take the kind of photographs I wanted to make. I tried reconstructing the parts of the world that had been discarded, abandoned, or thrown away. Ultimately I was looking for some idea of real and beauty rooted in the world we find ourselves in now.

Richmond St and Dinsmore Place, Cypress Hills, Brooklyn, NY © Sergio Purtell

I have always printed in a very open style, which was definitely influenced by my time at Yale. I remember that Richard Benson gave me a piece of material used in offset printing— the equivalent of a double 00 filter — that I would use to flash the print as a final touch to fill in any potential too-bright highlight. Also, I would split filter my prints. I can tell you that all this was incredibly tedious and time-consuming, but in the end, it would yield these beautifully open prints, with every possible midtown and a touch of black in the shadow areas and compressed highlights.

Gowanus Canal and 3rd St, Gowanus, Brooklyn, NY © Sergio Purtell

My book Love’s Labour came out in 2020, and I have been ruminating about publishing a second book — although keeping a business (BWonW.com) running during COVID has taken up most of my time and energy. For now, I post on Instagram (although I don’t post new photos as much as I should) and have an extensive website for those interested in looking.

Lee Ave and Flushing Ave, South Williamsburg, Brooklyn, NY © Sergio Purtell

Lincoln Ave and 138th St, Bronx, NY © Sergio Purtell

All photographs were made ranging from 2008 to 2014 © Sergio Purtell

Sergio Purtell - Edward Mapplethorpe, 2020 (Color portrait at top of post)

You can see a plentitude of more photos by Sergio on his website here: sergiopurtell.com His book published by Stanley/Barker, Love’s Labour is currently sold out. You can follow Sergio on Instagram here: @sergio_purtell

⇣⇣⇣ Next Profile: Ryan Frigillana ⇣⇣⇣

Ryan Frigillana

Ryan Frigillana’s work reveals a rich sensitivity to nature and intimate and incisive explorations of family, migration, and identity.

I first came across Ryan Frigillana’s work this past spring when one of his images of the Orchid Show at the New York Botanical Garden was published as the ‘Go opener’ in the New Yorker magazine. It was a dazzling photo of mirrors and orchids that showed me the beauty of nature - of flowers - presented in a new, fresh way, as were the outtakes he shared on his Instagram. Looking up Ryan’s website and Instagram, I was rewarded with more photos showing his rich sensitivity to nature along with intimate and incisive explorations of family, migration, and identity. The connections between family and nature are often explicit in his work and made me consider the idea of family as ecosystem - and what it can mean to move people born or raised in one environment to another. While we can all thrive in a new environment, the initial months and years of displacement can often prove difficult. When we have at last made a flourishing life in a new place, where does that thing inside us go that still misses the soil where roots first grew?

Broken Tractor, 2022. From the series, Manong. © Ryan Frigillana

I asked Ryan to tell me about his path into photography and the visual arts:

I was born in the Philippines and immigrated to the States with my family when I was about three years old. I don't come from an art background. I was groomed to have a career in healthcare from a young age, but I had little interest in the sciences, and I was terrible with math. Because of the language barrier growing up, I had difficulty making friends, so I took to sketching, and making comics, and writing poetry. Pablo Neruda was a monumental figure for me; his writing and way of visualizing the common world played a huge role in how I developed my sensibilities early on. I have always been an expressive person, but I never considered photography an artform until I was much older; the camera only served a utilitarian purpose in my household for memorializing moments and milestones. I took an Intro to Photography elective while I was in nursing school, and that was my first real taste of it outside of that context.

Reflection, 2022. From the series, Manong. © Ryan Frigillana

My interest in the medium blossomed when I bought my first camera (a Nikon FE) and taught myself how to process B&W film at home. At this point, I had dropped out of nursing school and started working a job in horticulture, which I did for several years. In the meantime, I learned to develop my eye by photographing my family, and by devouring photobooks and films (Stanley Kubrick, Terrence Malick, and Wong Kar-wai were huge influences). Oddly enough it was during this day job in horticulture, where I found myself staring at plants all day, that I learned to truly pay attention to my surroundings, to recognize the fragility and wonder in the smallest things—in shapes and curves, and in the movement of light and shadow. That job taught me how to be present with myself, to slow down and appreciate stillness. I began to observe the expressive gestures of plants—in the ways they would droop, or arch upwards in the sun, or how they would dry, wither, and transform. Training myself to find intimacy in the inanimate translated into how I observed and photographed people. Those years were formative for me in developing my visual sensibilities, but I still needed to develop a vocabulary of skills and critical thinking to match. After a long hiatus, I decided to enroll myself back into school to study photography full time.

Starved, 2020. From the series, The Weight of Slumber. © Ryan Frigillana

I joke that I became a photographer because I'm too impatient to draw or paint. There is some truth to that. What I love about photography is its immediacy and ubiquity. Anyone can make a photograph quickly and easily, but to create images with intent and to construct meaning out of an already-hyper-visual world is a challenge that I relish. My excitement for the medium lies in its slipperiness and its serial nature, and the potential that can be born from all that—that's what keeps me coming back to it. Images are everywhere, but you can't really pin them down because our relationships to them change over time and place. They are like little seeds that contain a dormant life. Where that seed is planted, contextually, will determine what meaning I am able to harvest from it later. I have many images collected in my archive that I like, but they don't yet have a "home" so to speak.

Direction Home, 2020. From the series, The Weight of Slumber. © Ryan Frigillana

When it comes to my praxis, I am at the point where I've found the itch that will take me a lifetime to scratch. I'm deeply invested in using photography to process my identity as a Filipino-American and employing this language as a catalyst for dialogue—to build community, connection, and understanding. My mother used to photograph our family as her way to celebrate and remember ourselves; I hope that what I’m doing with a camera today honors that spirit and much more. I am currently working on my next long-term project titled "Manong" that engages with the overlooked history of Filipino migrant workers in the U.S., using my own family to explore themes of generational labor and faith. I aim to publish this work as a book in the distant future.

Father, 2021 / A Heaven We Share (diptych), 2022. From the series, Manong. © Ryan Frigillana

My relationship to photography is one that’s in constant flux, but it is through these changes that I grow and deepen my connection to it. I've gone through many phases of interest in my work, from street, to still life, to documentary and conceptual work, etc. — but it’s all vocabulary building, and all ongoing. In the end, these experiences only serve to strengthen my relationship to my craft and help me better understand my position within it. Your ability to create is one thing no one can ever take away from you, so why not try everything? Throw yourself into your practice—suck at it, exceed, and suck at it some more. Keep working until you find yourself saying what you really want to say, not what others want to hear. But to arrive at that point, you just need to keep making. Half of the time, I don't know what I'm doing; I never have it all figured out. But I allow the act of creating to guide my steps. I can have all the greatest ideas in the world, but I need to try them to see where they lead me next. When I’ve done far more failing than succeeding, then I think maybe I’m on to something worthwhile...hopefully. But regardless of process, I am reminded to always begin from a place of genuine curiosity—a place that is authentic to me.

Knowing Good and Evil, 2018. From the series, Visions of Eden. © Ryan Frigillana

The House They Built, 2022. From the series, Balikbayan. © Ryan Frigillana

Protector, Predator, 2021. From the series, Manong. © Ryan Frigillana

False Idols, 2020. From the series, Visions of Eden. © Ryan Frigillana

Family Tree, Emme’s Painting (White Picket Fence), 2022. From the series, Manong. © Ryan Frigillana

Ryan Frigillana (he/him), b. Iligan City, Philippines, is a New York-based visual artist working with photography and image archives. His work reflects on the construction of familial identity, history, and home as a first-generation American.

He is the author of two monographs: Visions of Eden (self-published, 2020) and The Weight of Slumber (Penumbra Foundation, 2021). Select awards include a MUUS Collection / Penumbra Foundation Risograph Print & Publication Residency, the NYFA / JGS Fellowship for Photography, and being selected for the 2022 NY Times Portfolio Review.

He is open for projects and commissions.

⇣⇣⇣ Next Profile: Christian Michael Filardo ⇣⇣⇣

Christian Michael Filardo

Christian Michael Filardo is a Filipino American visual artist, composer, musician, poet, and sculptor currently living and working in Brooklyn, NY.

I love the world Christian Michael Filardo describes in their photos. It’s saturated, surreal, and questioning. Take Christian’s view of winter trees against a sunset sky - In Christian’s hands, a sunset is not color enough - so branches get splashed with red light transforming a dark silhouetted latticework of branches into a vivid vascular system that almost seems to beat with the universe's pulse.

Why do tree branches look like veins? What is that universal pulse that acts on all living beings? Why is it that we exist at all? Why is there something, not nothing? Why do we build things like dollar stores when death is just around the corner or heroicize our humanity when the reality is most of us are just trying to get through life with a big gulp from the 7-11 down the street?

Untitled, 35mm Color Film © Christian Michael Filardo

Our natural world and our human-made worlds are both such deeply strange and beautiful places, and yet most of us take it all for granted most of the time. I’m glad Christian’s photos remind us to live in the mystery and not the mundane.

I asked Christian to tell me more about their journey and practice in photography:

I first started making photographs in Sedona, Arizona while in high school. We were lucky enough to have a black and white darkroom there. Note, this was a while ago. I’m 30 years old now. Though it wasn’t until I moved to Baltimore, Maryland after college in Phoenix, Arizona that I began to make photographs more “seriously”.

While at Arizona State University I studied under Michael Lundgren who was a major influence on my photographic style and laid the foundation for how I sequence photographs today. However, I pursued a degree in intermedia art with a focus in performance while in school.

When I moved to Baltimore after university I had no studio, no money, no car. I was desperate for work and doing the classic door-to-door, application overload that one does when they move to a new city. I felt as though I had lost my art practice so I pivoted. I started carrying a Nikon Coolpix A, around and making digital images. It became compulsive. Everywhere I walked the camera came with. It became a salvation for my art making. I suppose for the camera nerds I switched back to shooting primarily 35mm film color film when I moved from Baltimore to Santa Fe, New Mexico in 2015. That is also to say, camera, film, lens, none of it matters. The best camera is the one that you use to make images.

Untitled, 35mm Color Film © Christian Michael Filardo

For me photography has always been about using the camera to critique modernity and place focus on the esoteric in hopes of forming a new photographic language and visual universe. Since I walk everywhere I am constantly in a state of flux, the otherwise banal and mundane become an ecosystem, something that changes and can be used to make gestures toward artistic and political ideas. Ideally, these images become a line in some sort of visual poetry. Though, there is a lot of garbage to sift through. It’s seemingly endless, the archive, ever growing. Ultimately, I hope to use photography as a tool to comment on art history, science, capitalism, global warming, human functionality, spirituality, and the surreality of being.

Untitled, 35mm Color Film © Christian Michael Filardo

That being said, I think photographers need to think less about picture making and look at more painting, read more poetry, watch more films. Photography is so young, its history so short, if it’s to ever be truly accepted into the fine art world it needs to acknowledge the history of it more. Perhaps that sounds ignorant or arrogant, maybe both. Though, I am talking on a micro level. If the general photographer spent less time talking about gear and more time talking about art we would have a lot more images that function beyond the photographic conversation. Gosh, whenever I do these I feel so serious like I come off too intense. I assure you I am a fun person to be around.

Untitled, 35mm Color Film © Christian Michael Filardo

I usually don’t love to talk about it but people always want to know, why flash? Why vertical? Flash, first and foremost is the ability to add an additional light source ad infinitum to any image you’re making. It can be useful for placing an emphasis on the foreground background relationship. To me, it’s useful for dividing a composition, for drawing attention to subject matter, for adding an odd visual component to a potentially otherwise drab scene. My images are primarily viewed on cell phones, that’s our reality, the screens are vertical. It’s how most of us see the world, so I record the world as such, vertically.

Untitled, 35mm Color Film © Christian Michael Filardo

Outside of photography I write poetry and have somehow managed to scrape by a living in New York City for the past five months on my practice alone. It’s not always fun but I am free, I find happiness, I push away monetary woes by throwing I-CHING, going on walks, talking to my peers, and reading tarot. It’s all about keeping the vibe up I guess. If it wasn’t for photography and writing I wouldn’t be free to make art, to approach life as though everything has the potential to be art, to be lost, to be a fool. I am blessed.

Untitled, 35mm Color Film © Christian Michael Filardo

My advice for anyone getting into photography as either an art form, hobby, or work is to always carry a camera and be absolutely relentless on the shutter. Waste film, waste memory card space, not everything will be good. You will lose money, you will lose time, it’s all an investment in your archive. If you do something long enough you will have a breakthrough, even if it’s just for you and you alone. Not everyone needs to see your images, life really is a divine joke after all. Nothing is precious, time passes us all, enjoy it baby.

My show “The Backyard of Heaven” is up atNightclub in Minneapolis, Minnesota until May 8, 2022. My most recent zine “The Purple Pill” is nearly sold out on Pomegranate Press should it be of interest to anyone.

Christian Michael Filardo is a Filipino American visual artist, composer, musician, poet, and sculptor currently living and working in Brooklyn, NY. Filardo writes critically for PHROOM and photo-eye and is a co-founder of the Richmond-based art space Cherry. Filardo released their first monograph, "Gerontion", with Dianne Weinthal at the Los Angeles Art Book Fair in April 2019. Since then, they have released numerous books and zines across multiple publishers, including Pomegranate Press, Udli Editions, and Phinery.

More of Christian’s work can be viewed on their website or their Instagram.

The photo of Christian at the top of the post is by Willa Piro.

Untitled, 35mm Color Film © Christian Michael Filardo

⇣⇣⇣ Next Profile: Jesse Warner ⇣⇣⇣

Jesse Warner

Jesse Warner is a New York City-based photographer who makes fun and funny and sexy portraits of people and food that are absolutely delightful.

While I’ve long been impressed by professional food photographers’ abilities to style and photograph food in a way that makes food look beautiful and special and precious, those photos most often reflect a marketing mindset and relationship to food that I just don’t have. I moved to NYC to eat food not sell it. I like to get messy with food. I like having fun with food. My mindset towards food is I once bought a domain called mouthcooking.com because I was so sure that would be the next food trend…recipes where you get different ingredients and combine them in your mouth to make the finished dishes. (Take one bite of banana. Hold in mouth. Take one bite of dark chocolate bar. Chew freely.) If anyone could make my messy stupid idea into an actual new trend, it would be Jesse Warner. His photos of people and food are so fun and funny and sexy and delightful that there’s only one word that can sum up how I feel about his work…DELICIOUS. I asked Jesse to tell me more about his path in photography:

Drunk Pizza Lust, Brooklyn, NYC. © Jesse Warner

I thought I wanted to be a chef or photojournalist, and I guess I ended up somewhere in between. When I moved to this city, I took a job at a café in Long Island City that prides itself on being a community space that actually pays minimum wage(anything over 30 hours is cash!) with an abusive boss. I had only enough money for a one month sublet in Astoria in a freezing February and had no money for the subway and would buy off-brand poptarts from the dollar store and give one to the homeless man at the R train. My uncle was a sportscaster for a radio station and found out that I was interested in photography and gave me his old Canon Rebel G and some expired film to start. Since I had no friends, I started interviewing random people on the street that looked interesting and set up photoshoots with some truly odd-ball craigslist ads. For some reason, I found comfort in Flushing, Queens and would frequently go there and take street portraits and eat at New World Mall. Most of my work aims to express how food is a reason for people to come together. My early photography was me exploring a city new to me, and pinging the world to say "I exist".

I've worked with and have been attracted to food my whole life. My parents did not know how to cook, so I had to teach myself. I would watch Iron Chef Japan religiously and would make gigantic messes in the kitchen trying to recreate dishes in pursuit of flavor. I thought I hated food for the longest time. I grew up eating things like 98% fat free burgers with no salt or pepper, on a George Forman grill with raw onion, raw mushroom, lettuce, and thick cut off-season tomato rare on a soggy sesame seed bun. I started working in kitchens after discovering that eating out or making my own food was the key to a life worth living. I started as a deli boy and somehow years later worked three years at a Michelin Starred restaurant here in NYC as a Kitchen Lead. During the pandemic, I focused more on my photography while also working at the farmers market and various catering companies. I like to keep my schedule fairly flexible to avoid the nine-to-five burnout which is very important to me.

My One Desire, Brooklyn, NYC. © Jesse Warner

One of the most parallel shoots references from cooking to film was climbing a ladder to get ingredients and measure them out on a scale and climb back up. To save time, I somehow mastered pouring oils, vinegars and all sorts of liquids from the top of the ladder into a tiny 6 pan and be able to accurately measure something out for a recipe. Chef would be pissed, but have nothing to say after I explained how much time I was saving and how I made zero mess. This inspired my shoots where I had a model pour oil and vinegar mid-air and captured it. I loved the way the flash captures liquids on film. The plate is a canvas. You have all sorts of out of these highly saturated right out of the box colors swirling around the plate and you want to make it look pretty. That's why I use Ultramax 400

Don't Cross the Streams, Brooklyn, NYC. © Jesse Warner

My breakthrough moment that food would be a recurring theme in my portraits is when I made a mess at work and the head chef came over to make a big scene. I jokingly said "I'm an artist, I was just trying to paint with colors". I went on to say that I should make a Youtube channel where I leave the top off blenders in a white room and how there's definitely an audience. Somehow he didn't murder me, but in that moment everything came together and nothing he said could have made me feel anything other than pure joy. Here I am making these pretty little sauces and these pretty little plates and all I want to do is make messes. My work is me saying "so what?" to everyone who has ever called me "Messy Jesse" since kindergarten, because at the end of the day, I'm having a blast.

Ramen Noodle Bath, Brooklyn, NYC. © Jesse Warner

The most exciting photo books to me are honestly old family photo albums including my own. My family is especially goofy and I'll constantly be chasing the candidness of being a colorful dressed kid in the 90's that does what he wants. My grandmother has an especially large collection of photo prints of people that is going to be a massive archive project sometime in the future. I think family photos, particularly on trips, provide that intimacy and comfort that allows you to be a true loose version of yourself and that's what makes a great photo.

Ronnybrook Romance, Brooklyn, NYC. © Jesse Warner

You can buy stickers, t-shirts, and postcards with Jesse Warner’s photos on them at his online store here.

Follow Jesse on Instagram: @warnerjesse Keep an eye out for Jesse’s new website, coming soon here.

Portrait of Jesse Warner at top of post: © Shandy Tsai (@shandytsart)

⇣⇣⇣ Next Profile: Tracy Dong ⇣⇣⇣

Sofie Vasquez

Sofie Vasquez (b. 1998) is an Ecuadorian documentary photographer born and raised in The Bronx, New York. Her artwork explores the mediums of photography and filmmaking to create long-term projects focusing on narratives about identity, community, and culture.

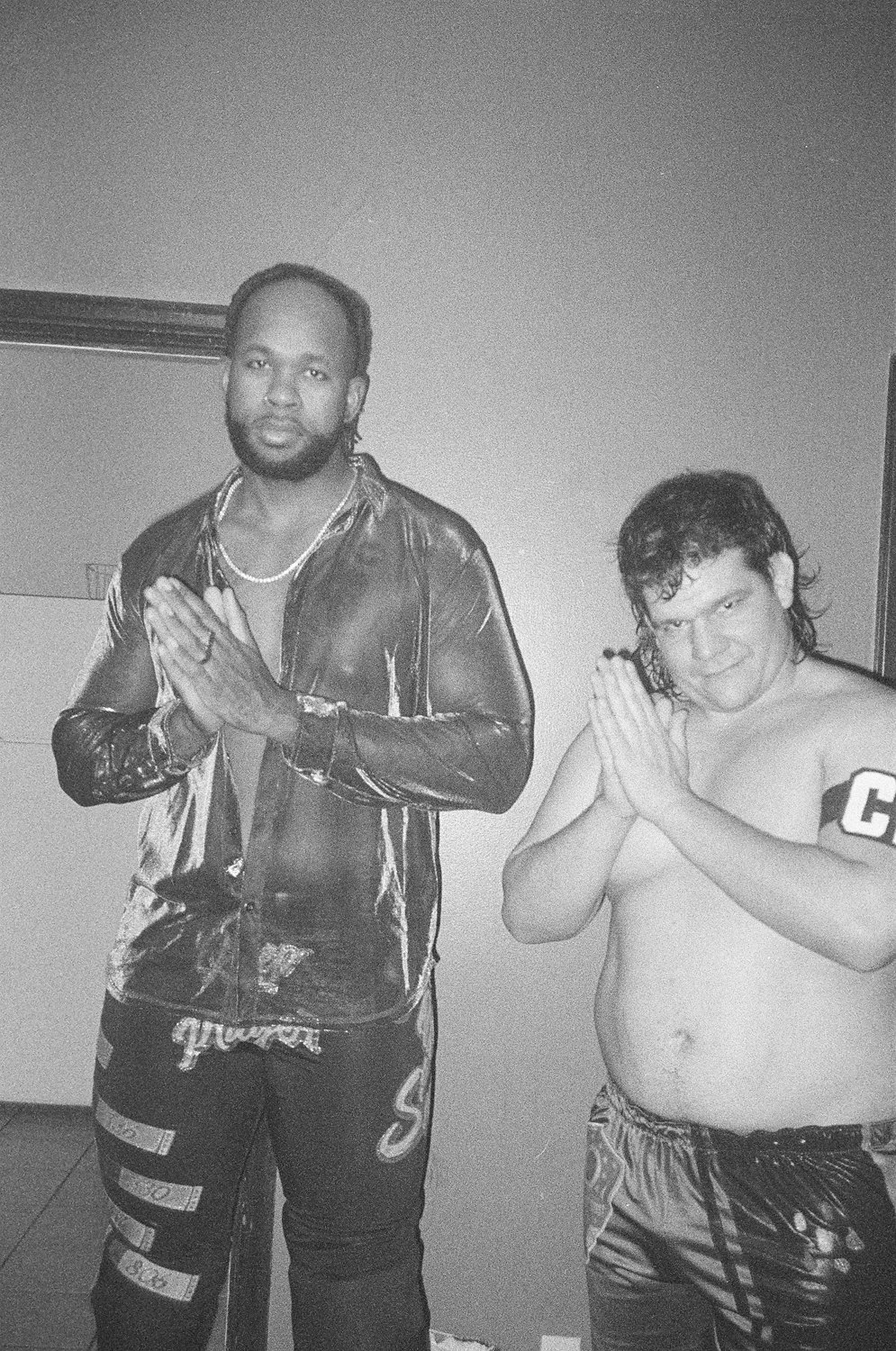

Dawoud Bey has said, “I make the work that I do in order to visualize the things that are important to me, and to make them matter to someone else.” If that’s one of the goals a photographer and artist should aspire to then Sofie Vasquez has succeeded tremendously with her compelling documentation of the indie wrestling scene. The wrestlers in this subculture are hugely passionate about wrestling, and Sofie matches their passion and commitment with documentation that captures not only the energy, blood, sweat, and tears of the wrestling matches, but also the excitement and interaction of the wrestlers with the fans, and, in some of my favorite photos in this body of work, the quiet, casual, and just plain fun behind-the-scenes moments that really help to humanize these stars, heroes, and villains of the wrestling ring. These are folks with big personalities, and Sofie’s images put those personalities and people on film with great love and respect.

I asked Sofie to tell us about her journey in photography, and how she got involved in documenting the wrestling scene:

Ironically enough, I wanted to be a filmmaker as a kid. My father was a film student in college when I was a toddler so I remember growing up surrounded by his books about cinema and always going to Whitestone Cinemas in the Bronx. So in my senior year of high school, I took video production and studied film history when suddenly, I found myself enjoying taking pictures instead of filming on the Canon camera we had for class. It was so addicting that I checked out the camera without permission every Friday to take it to concerts I was attending on the weekend - alongside video, I also had goals in becoming a music journalist so I would find my way into The Studio at Webster Hall or the Knitting Factory, and ask the booked photographers there if they had a moment to show me how to operate the camera.

And from there, that’s where the explosion of photography happened - it began with me exploring specific subcultures and discovering the photographers of their respective scenes. CJ Harvey, a film photographer from Pennsylvania who toured with my favorite indie bands, was my first favorite photographer before I knew who “the greats” were. Their work was my first introduction to documentary photography - to have a body of work following people who fascinated and inspired you. And at seventeen to nineteen, I had my sights set on being a music photographer because I loved music and the culture, so I started taking photography classes in community college and this is kind of where everything began to fall into place. I took Intro to Documentary, Narrative, and Photojournalism in my second year of community college (Thank you Prof. Towery) and I simultaneously began taking black and white film photography classes at ICP at The Point - I always credit and thank the community for teaching my photography. The community of music photographers who gave a dumb seventeen year old’s ramblings a chance of day, the teachers and teaching assistants pushed me when I got comfortable, and even the community of photographers who are my friends and colleagues today. Actively, we root for each other and lend aid, assistance, or just creative ramblings for us photographers.

I’ve been a wrestling fan since I was a kid. Ohioan wrestler Dean Ambrose was my hero. I once broke my arm trying to do an elbow drop, and at sixteen, there was a genuine interest in becoming a wrestler if I had found the right school. Wrestling is a chaotic and insane subculture that holds a sincerity to me, the same way it has for not only the wrestlers but for anyone who was once a wrestling fan. Since 2018, I have been a photographer in independent professional wrestling. At 19, I found it in a gym in the South Bronx, a mere 15 minutes from my home. From 2020 till 2021, I traveled with wrestlers across state lines to document their hustle, sacrifice, and commitment to this industry. It all began with my grandparents driving me to Atlantic City to go witness a wrestling death match by the beach. Then I went back on a coastal city bus, and soon those seats were replaced for cramped back seats in tiny packed cars going hundreds of miles out into the Midwest.

The life of an indie wrestler equates to that of a rock'n'roll star on tour, minus the unlimited budget provided by a record label. If you started training early, like most at 16, this is all you know and because this is all you’ve known, you’re willing to sacrifice everything for it. I’ve seen men without insurance collide their scarred bodies against light tubes, barbed wire, and doors on fire. I’ve been on 12 hour plus car rides for a one night only gig that could be a make it or break it opportunity. I’ve seen broke men, women, and non-binary athletes been stiffed on pay after they broke their bodies out in the ring. Yet, despite the shortcomings that would follow around anyone who is in pursuit of their dreams, I’ve been moved to tears by a crowd’s roar when a wrestler walks through that curtain. State to state, I've traveled with them with the intent to not only document their adventures to capture the friendships, the Americana, the glamor, and the hard work. All of the layers of professional wrestling that are wrapped into the lives of people I’ve deemed not only as my friends but as my biggest inspiration. I’ve tentatively dubbed this body of work Almost Famous: An Indie Wrestling Diary, and it completes a deep but intimate, understanding portrayal of indie wrestling and those involved in its world.

2022 is a full circle moment - I’m making a film about wrestling. The photographer finally learns how to film and edit like how I had anticipated all those moons ago but I’m superstitious and believe in perfect timing. I had to fall in love with photography first to truly enjoy, understand, question, study, and accept filmmaking, they’re not that far apart. They’re practically siblings. And because I like to overwork, I’m working on a book. Also about wrestling. Consider it the perfect bow to a long-term project - I’m not leaving wrestling but I want this hard work chronicled in a tangible body of art I can share with everyone. There are other projects - I’m thinking roller derby, boxing, demolition derby, and horror conventions - I want to sink my teeth into, in 2022.

My genuine advice to a photographer is - fall in love with the process. Trust your gut, trust your story, trust yourself and your vision and your choices, and whatever path you take in photography - whether it be journalism, editorial, experimental, documentary, fine art, or just a little mix of the in-between - always find yourself wanting to do it all over again. Breaks are ok, remember that burnout is very real and you taking a pause to step away or even step out of your comfort zone is going to be the best decision for yourself and even your art. Believe in what you’re doing, but also leave some room to learn. Photography is still pretty young alongside the other mediums of art - make a cyanotype, be vulnerable in front of the lens and take self-portraits, try a point-and-shoot or a 4x5 camera, take a continuing ed or after school class if you can afford it.

I once overworked myself so much I didn’t touch my camera until I had gigs. And sure, I did the work, and I had fun. But it was temporary and felt stale - I had to say “fuck it”, buy a roll of film and take my film camera on my errand run and just shoot what I saw and what I liked. Not for a long-term story or project, it doesn’t always have to be project-oriented or for an assignment, don’t forget to shoot for yourself.

Follow Sofie Vasquez on Instagram: @bullsinthebrnx, and check out her other bodies of work on her website here.

Pre-order a copy of her 2021 wrestling zine Estoy En Mi Peak here.

Photo at top of post: Self Portrait, in quarantine, 2020. © Sofie Vasquez

↓ ↓ ↓ All Photos in this post © Sofie Vasquez ↓ ↓ ↓

Brooklyn native Big Game Leroy makes his debut in San Antonio, Texas, 2021. © Sofie Vasquez

Brooke Valentine at her Mania Week debut in Tampa, Florida, 2021. © Sofie Vasquez

Holidead defeats Kaia McKenna at the Voltage Lounge in a 24 hour wrestling show, 2021. © Sofie Vasquez

Canadian wrestler Jody Threat at the Amvet Hall in Yarmouth, Maine for Limitless Wrestling, 2021. © Sofie Vasquez

MV Young in Texas, at Heavy Metal Wrestling, 2021. © Sofie Vasquez

Weber Hatfield and Big Dan have an 80s montage moment in a barn in Pennsylvania, 2021. © Sofie Vasquez

PB Smooth and Dominic at Enjoy Wrestling, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. 2022 © Sofie Vasquez

Sofie Vasquez (1998) is an Ecuadorian documentary photographer born and raised in the Bronx, New York. Her artwork explores the communities within subcultures through a personal perspective and has been featured in The New York Times, exhibited at the Bronx Museum of the Arts, the Bronx Documentary Center, the Ecuadorian-American Cultural Center, The Clemente Soto Vélez Cultural and Educational Center, the Shirley Fiterman Art Center, the DGT Alumni Association Gallery House, Photoville and En Foco Inc.

Sofie is an alumnus of the International Center of Photography's Community Fellows, and is a part of the first graduating class of the fellowship, 2018-2020. She was a student at The City College of New York until the COVID-19 pandemic forced her to pause her studies. She is currently a Bronx Documentary Center Films Fellow and a freelance traveling documentary photographer.

Website: sofievasquez.squarespace.com Instagram: @bullsinthebrnx

⇣⇣⇣ Next Profile: Raphaël Gaultier ⇣⇣⇣

Raphaël Gaultier

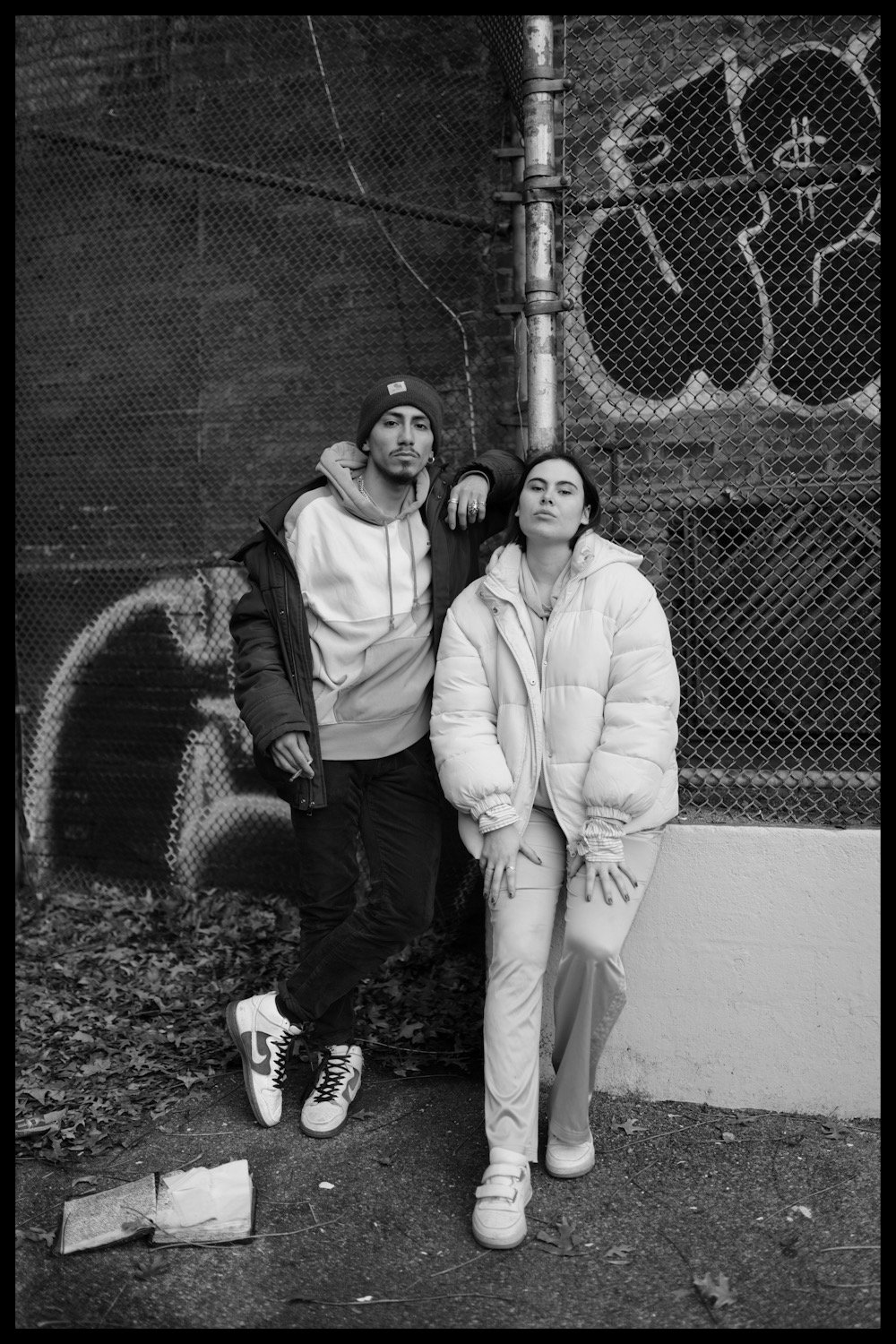

Raphaël Gaultier is a self-taught freelance portrait and documentary photographer from Seattle, WA currently based in Brooklyn, NY working across a variety of genres to capture the intimacies of daily life. His work is concerned with the concept of home, whether that’s found in spaces, people or objects that speak to who we are.

When I look at Raphaël Gaultier’s photographs I feel like I’m seeing the kinds of images that come into being when a photographer is trusted to be present for gestures of simple intimacy or moments of quiet vulnerability. They’re not found images, they’re revealed images - pictures that emerge over time in light the way landscapes emerge underneath a rising morning sun.

In our often anxious and uncertain times, I appreciate the thoughtful beauty and presence of his images more than ever. I asked Raphaël to tell me a little about his journey in photography:

For a long time growing up I always thought of myself as the least creative in my family. I want my work and my journey to be a testament to others that anyone can pursue something they’re passionate about if they put in the time with their craft. I had no photography education growing up - it wasn’t until midway through college that I picked up a camera to start taking pictures after I tore my ACL playing sports. It was that necessity to express myself when I wasn’t able to do the things I love that helped shape me into the photographer I am today.

Oftentimes, what I’m trying to express in my work is to look at everyday things and occurrences and appreciate them for what they really are. My world revolves around the people I spend my time with and the places I habitually venture, and I want my work to be a representation of the comfort that comes from our everyday routines. There’s an intimacy I often capture in my work that I think shows the kind of upbringing I had. I’m glad my work and who I am are so closely tied - it feels authentic to the stories I’m trying to tell.

I prefer to shoot on film because it slows down my entire process for each photo I take. The speed at which artists are expected to produce, share, interact with, brainstorm, and improve on their work is highly unsustainable and leads to less thoughtful work. My work and my process is focused on doing the opposite of that. By using a medium format camera and meticulously scanning in each photo I take, I’ve slowed down my process to care for each step in the process. I’ve found that being more intentional with the ways I work in medium format has helped me become a more thoughtful photographer when I pick up a digital camera as well.

The speed at which photographers (as well as other artists) are expected to produce and share work is something I think is completely backwards in the industry. I’d like to see more thoughtful, long term projects that are backed by brands and publications that have the finances to support independent artists. I think we’d see a big difference in the industry’s mentality to constantly pump out work, and the quality of meaningful work that would arise out of it. I hope there will be things that help address this problem of overwork in the photographic community in the years to come.

Follow Raphaël Gaultier on Instagram: @raphgaultier.

Photo at top of post: Self-portrait

↓ ↓ ↓ All Photos in this post © Raphaël Gaultier ↓ ↓ ↓

Kat and Noah, Seattle, WA. 2021 © Raphaël Gaultier

Helen, Seattle, WA. 2020 © Raphaël Gaultier

George and Miguel, Seattle, WA. 2021 © Raphaël Gaultier

Ophelia, Seattle, WA. 2020 © Raphaël Gaultier

Soft Light, Portland, OR. 2020 © Raphaël Gaultier

Funeral, Maui, HI. 2021 © Raphaël Gaultier

Raphaël Gaultier is a self-taught freelance portrait and documentary photographer from Seattle, WA currently based in Brooklyn, NY working across a variety of genres to capture the intimacies of daily life. His work is concerned with the concept of home, whether that’s found in spaces, people or objects that speak to who we are. His work has been featured in i-D magazine, Pitchfork, The Nation, The Seattle Times, as well as several other books and publications. Raphaël has worked as the co-founder and editor of Human Condition magazine, a publication centered around providing resources and uplifting young artists in Seattle, as well as Associate Creative Director of Seattle-based retailer LIKELIHOOD. He’s been freelancing as a photographer since 2020.

Website: raphaelgaultier.com Instagram: @raphgaultier.

⇣⇣⇣ Next Profile: Cat Byrnes ⇣⇣⇣

Cat Byrnes

Cat Byrnes is an artist whose photographs reflect a graceful, gentle, and generous stance towards the world she inhabits and explores.

Voltaire ended his novel, Candide, with the line, “We must tend to our garden”. In these words are a suggestion that whatever crisis is going on in the world at large it’s also imperative to care for and pay attention to the good in our immediate surroundings - things like family, friends, and community. These are the flowers and food that nourish our souls and enrich our hearts. In Cat Byrnes’s photographs, I sense something of a gardener tending with care and love to her city and her people - an expansive and sometimes wild garden whose ephemeral blooms of beauty and intensity she’s able to catch with her camera and share with all of us. I asked Cat to tell me more about her work:

I create photos to communicate. Like a latent voicebox, it symphonizes with everything I make. Over the years, as my perspective changes so does my work. There are times that I wish to remain still in the harmonious confines of myself. But life demands that I contend with the chaotic and fleeting passage of time. I believe my photography seeks to bridge the juxtaposition between these two seemingly disparate yet essential parts of the human condition. Street photography challenges me to stand apart from others to capture precious, fragile moments in time that are so fleeting they pass thoughtlessly through our hands like grains of sand. I am essentially apart with my viewfinder, yet never wholly so.

The spontaneous compositions that fall right into place get me the most excited. I enjoy the process of capturing chaos unraveling in front of my eyes, it is a good reminder that you will never get exactly what you expected from a photo. Sometimes it is even better. For example, one of my favorite photos chosen for this newsletter was taken on my rooftop in Brooklyn. It was taken during the Black Lives Matter Marches in the Summer of 2020, at the peak of Covid. The mass of protestors cascaded through the city past Brooklyn and towards Manhattan. Onlookers watched their ascent with gregarious awe. Each of us stood upon our rooftops, a city of isolated archipelagos, while the protestors continued as a united current for the sake of societal change in the face of sickness and death. The composition mirrors the story perfectly.

One of my main goals is to publish a photo book and have my first solo show.

This upcoming spring I have two of my photos included in Pomegranate Press’s community group book, NOTHING LEFT BUT HEALING, a corresponding show will be held at Agony Books in Richmond, VA.

Over the last few months, I have been working on a new painting series influenced by my past experiences with hiking, foraging, and gardening. These works depict wild landscapes and environments drawn with oil pastels on unprimed canvas. The main theme represents the push-pull duality between living in the city yet longing for nature.

Cat Byrnes is a third-generation artist living in New York City. She received her BFA from Pace University in Photography and Painting with minors in Anthropology and Art History. She currently works at a film lab in Manhattan.

Follow Cat Byrnes on Instagram: @catbyrnes (photos) | @catbyrnesart (paintings).

Photo at top of post: Self portrait, New York City, 2021 © Cat Byrnes

↓ ↓ ↓ All Photos in this post © Cat Byrnes (@catbyrnes)↓ ↓ ↓

New York City, 2018 © Cat Byrnes

New York City, 2021 © Cat Byrnes

New York City, 2019 © Cat Byrnes

Brooklyn, 2020 © Cat Byrnes

New York City, 2019 © Cat Byrnes

Kingston, Pennsylvania, 2021 © Cat Byrnes

⇣⇣⇣ Next Profile: Samantha Box ⇣⇣⇣

Samantha Box

Samantha Box is a Jamaican-born, Bronx-based photographer whose work is an articulation of the ways in which identity – and by extension, community, networks of care and survival, ideas of home and belonging – are formed within spaces of sociopolitical and physical liminality such as Blackness, queerness, and diaspora.

Samantha Box is a photographer whose lush and layered work intrigued me and drew me in as soon as I encountered it. I was reminded of something photographer Alejandro Cartagena said in Sasha Wolf’s great book Photo Work:

“I think in layers. The more layers a project has, the more possibility there is that one of those layers will relate to someone. Something like this: The project needs to be aesthetically, technically, conceptually, and historically relevant; have a personal connection, pull toward some kind of social commentary, be able to show personal and artistic vulnerability; and so on.”

Looking at Samantha’s work, I say to myself, “yes yes yes yes ” because her images are so beautifully answering Cartagena’s wishlist. What also struck me about her work, particularly in her Caribbean Dreams - Constructions series is the way the photographs break open a historical form in a relevant way not simply as critique, but to enlarge it and make the form more expansive. Samantha’s images remind us that the real power of artists is to see the world not simply in categories and niches, but in all its complexity and creativity and beauty and pain and sadness and possibility and all the places and possibilities in between. I asked Samantha to tell me a little more about her work and thoughts on photography:

Tell me about your work

The main idea that undergirds my work is an articulation of the ways in which identity – and by extension, community, networks of care and survival, ideas of home and belonging – are formed within spaces of sociopolitical and physical liminality such as Blackness, queerness and diaspora.

I love full images where all parts of the frame are actively being used, an image that carries a satisfying sense of lushness and tension.

How has your work helped to shape the photos you make?I’m really fortunate in that most of my work that I’ve engaged in to support my photography has informed my work. For example, for much of “The Shelter, The Street”, I was working at Contact Press Images. I spent a lot of time working with, and learning from, amazing photographs, and this translated directly into my work at Sylvia’s Place.

After, I began teaching photography to at-risk queer and TGNB youth of color at the same time that I began to make the images that comprise “The Last Battle.” Some of the young people that I photographed at Kiki ballroom functions were also my students. It was my students’ work – and community documentation made by the wider Kiki scene - that prompted me to confront the limitations of documentary practice: among them, who has the authority to create a narrative of a community? In other words, I realized that the Kiki Scene was expertly doing the work of documentation already, and so, I decided to take a step back, which partly informed my decision to go to graduate school.

I still support myself through teaching. Researching, editing, and presenting work for in-class lectures – with an emphasis on destabilizing the historical and contemporary white/European/American/male canon - means that I look at work made by a wide range of people, working in a wide range of styles/practices. Regarding my practice, it means encountering work that inspires, summons indifference, or sometimes repulses. This means that I’m constantly thinking of where my work stands, how it’s in conversation with other photographer’s work, thoughts, and practices. All of this shapes my work.

Is there a photo book that’s held a lot of significance for you as a photographer?Milton Rogovin’s “Triptychs: Buffalo’s Lower West Side Revisited” is a book – and series - that had a profound impact on me when I first saw it; the same is true of the next (unpublished) iteration of this work, which is a series of quadtychs. This work presented a way of working with a community over time - of making quiet, nuanced, thoughtful and collaborative pictures - that I was hungry for when I encountered it in 2005, and which, at that time, was vanishingly rare. Whenever I think about the arcs of the lives in these multi-part images – the births, deaths, connections, estrangements, generations - I am deeply moved.

Is there anything you’ve had to ‘unlearn’ about photography to make the artworks you now make?Apart from composition, exposure and lighting, I’m actively trying to unlearn everything.

What advice would you offer to others who see your work and want to get into photography?The image comes first, not the camera, analog/digital, social media. Work at images that are singularly, visually your own. Share this work with people whose work you respect, and who you can trust with your mistakes and questions. Grow together and support each other!

Has the pandemic influenced your work?From the early days of our current moment, I realized that the only thing that I could count on was my work. I have learned to trust myself, to follow my ideas, and to give myself a wide berth for experimentation and iteration.

Looking ahead, what are some goals or hopes for your own work in the years to come?In the next year, I am determined to solidify my studio practice, and to resolve this sense of disconnection between the different bodies of work that make up Caribbean Dreams. I’d also like to start thinking of the best way to archive all of my INVISIBLE work.

Lastly, we’d love to know about what’s happening with your art practice right now? Where, besides the web, might people encounter your work?My work is currently in a number of places: Subject-Object at St. Lawrence University (until 2/26), Eco-Urgency: Now or Never Part ll at Lehman College Art Gallery (until 4/23), and Picturing Black Girlhood: Moments of Possibility at Express Newark (until 7/6). A portrait of artist Zachary Fabri – part of Beyond the Flat, a collaboration conceived of by artist and activist Ted Kerr – will be shared at Zachary’s performance at Weeksville on 3/19. And, I will be having a solo show at Light Work in the Fall!

Follow Samantha Box to see more and stay up to date!

Photo at top of post: Construction #6, 2019 © Samantha Box

↓ ↓ ↓ All Photos in this post © Samantha Box (@samantha.box) ↓ ↓ ↓

Construction #1(3), 2018 © Samantha Box

An Origin, 2020 © Samantha Box

Multiple #3, 2019 © Samantha Box

Realness, The Miami to New York Ball, November 2013 © Samantha Box

Face, The This is It Ball, April 2014 © Samantha Box

Team Performance, The Marciano Ball, October 2015 © Samantha Box

⇣⇣⇣ Next Profile: Troy Williams ⇣⇣⇣

Troy Williams

Troy Williams is a fantastic street portraitist.

It's an unusual and difficult thing to ask a stranger if you can make their photograph. Many people might rightfully be suspicious and skeptical of a request like that. Yet despite their suspicions, some people do say yes. They agree to trust you and be vulnerable in front of your camera. And by giving you their trust and being open, you now hold a responsibility as photographer. You have to make an image that does some justice to the trust they’ve placed in you. And as difficult as it may have been to ask for a photo in the first place, it’s even more difficult to make one that sings.

It’s now your task to make a photograph to the best of your ability that describes the person in front of you. Not necessarily to make a flattering image, but to try and make an honest and truthful image - a photograph that holds some of what you saw in the person when you decided to approach them, and some of what they gave you as they arranged themselves for your camera, and some of what you created together in the act of making a photograph.

Knowing how difficult this practice is, I was blown away by Troy Williams’ street portraits - these photographs are absolutely wonderful at making so many complex variables dance in a single image and serendipitous encounter - light, background, pose, gesture…Everything just hits me as right with these images, and maybe most importantly I feel like I’m connecting to the people in the photographs. I feel like I have some intuition of who they are, and while I may be wrong about that intuition, I at least know, thanks to Troy, about their light and humanity on the day Troy photographed them. I love seeing people through Troy’s eyes, and I can’t wait to meet more. He’s a photographer you should be watching.

I asked Troy to tell me a little about his motivations in making the images, and what he learns from these fleeting interactions with strangers:

Isn’t it lovely to be able to look deeply into someone’s eyes and be able to hold that gaze for as long as your mind wants to wander? What a gift it is to have an intimate and spiritual interaction with another. And when it happens with a complete stranger who shows you themselves unguarded, vulnerable, confident, and with a graceful trust, one can’t help but wonder if that moment was touched by the connecting energy that makes us live and breathe. My fascination, specifically with street portraiture as an action of faith, has led me on a beautiful and emotionally satisfying journey.

As we have all experienced the overwhelming aspects of change during the pandemic, my post cocoon moment came when the light of safety began to show it’s ever changing face. My second act in the world of being a photographer began in the summer of 2021. Before the world turned upside down my inspiration for making photographs was based in evoking memories of moments lived and reimagined. Theatrical and cinematic representations of life in my rearview mirror. I was always looking towards the past. Once the lockdowns ceased and the vaccine was readily available with infection rates dropping, all I wanted to do was be close to people again. I decided that it was time to live in the present. Portraits became the proposition.

I am consistently awestruck with the connection made between the subject, the photographer and the audience, which in my belief, creates a community. It has the ability to bring forth the interiority of our desires, our faith, our aspirations, our apprehensions, our truth. It is this profound power that portraits have that brought me to my current version of myself. And just as important as my need to connect, I make these portraits as a way to honor and pay attention to the everyday people that I lovingly cross paths with. We are strong, resilient, creative and healing beings that have the power to lift each other up. We inspire when we live out loud with enthusiasm and compassion. Our surface shows so much of our spirit. A photograph is a beautiful vehicle between one soul to another.

Follow Troy Williams

Portrait of Troy Williams at top of post © Mark C. Wagner @thewarneraesthtic

↓ ↓ ↓ All Photos in this post © Troy Williams @trooooooooooooooooooooooooy ↓ ↓ ↓

⇣⇣⇣ Next Profile: Rafael Herrin-Ferri ⇣⇣⇣

Rafael Herrin-Ferri

Rafael Herrin-Ferri is an architect, photographer, and author of the photo typology All The Queens Houses which explores the eclectic vernacular residential architecture of Queens, NY.

I grew up in neighborhoods built by developers who named their new developments after the things they replaced (Great Oaks, Fair Lakes, Green Acres, etc.). The developers who built my neighborhood, and others like it, saved costs by offering just a few models of houses to choose from, painted in limited, muted palettes. For all the downsides of the 'Little Boxes' approach to real estate development, the consistency did provide a sense of security and stability.

Bay Ridge, Brooklyn. where I now live, is absolutely anarchic in comparison, and my first reaction to the aesthetic chaos was not enthusiastic. Honestly, it seemed ugly to me - too much of a disorganized hodgepodge. Over time though, I've come to really appreciate and even love the unexpected flourishes, strange brickwork, and quirky architectural surprises you'll find in a stroll around my neighborhood.

Architect and photographer Rafael Herrin-Ferri, who lives in Sunnyside, Queens, a neighborhood with an even more anarchic mix of styles and influences became fascinated with the organic and adaptive evolution of the residential architecture in his neighborhood, coming to see it as an 'urbanism of tolerance.' He embraced it and set out to document all the strange and wonderful houses and architectural juxtapositions he could find. That documentation became a popular Instagram account, and now a book, All The Queens Houses.

I love this portrait of Queens, and feel it's a perfect response to the cliche idea of New York City as a collection of ostentatious skyscrapers and Manhattan street scenes.

I asked Rafael to tell me a little more about his start in photography, and his project All The Queens Houses:

I’ve been making photographs since my junior year of high school, spent in Seville, Spain. My father had his friend bring me over a 35mm Minolta purchased at B&H and it really opened my eyes to the built environment.

I started All The Queens Houses to document the eclectic character of the Queens housing stock.

After making several hundred photographs exploring the neighborhoods I realized what a truly unique urban environment Queens is. I began to see my ongoing documentation as a project, came up with this funny title, and eventually enough material—and ideas—for a book.

I talked to a few of the homeowners while making the photographs, but not as often as I would like—there never seemed to be enough time since cloud cover was precious and Queens is enormous! On a couple of occasions I was confronted, wondering why I found their houses of such interest, but for the most part, after a brief explanation, they were very supportive. I even got a couple of “you’re doing God’s work” comments.

In terms of my professional work as an architect, making these photographs has confirmed my preference for vernacular architecture—especially residential vernacular architecture.

If I were designing my own house, I’d make one with a large balcony, an interior courtyard, and a patterned brick façade.

I consider All The Queens Houses an architectural project and a photographic project, and even though I now have a book of the work, I hope to continue the project on Instagram and in the real space of museum galleries one day, adding a video component to the documentation.

My book is available through most booksellers but if you decide to buy it, I hope you will choose an independent bookseller based in Queens!

“All the Queens Houses features over two-hundred color photographs representing the highly idiosyncratic housing styles of every neighborhood in the borough, from Astoria to Auburndale, Long Island City to Laurelton, and College Point to Far Rockaway.”

“Rafael Herrin-Ferri is a Spanish-born architect and artist living in Woodside, Queens. He received a B.Arch from Cornell University in 1996 and spent the following six years working in architectural studios in San Francisco and Barcelona—including a seven-month stint with the late great Catalan architect, Enric Miralles. He returned to New York City in 2003 where he realized two private house commissions inspired by the local fauna while working in various award-winning Manhattan design studios.”

Follow Rafael Herrin-Ferri

Photo at top of post: Portrait of Rafael Herrin-Ferri

↓ ↓ ↓ All Photos in this post © Rafael Herrin-Ferri / @allthequeenshouses ↓ ↓ ↓

Salmon-Colored Stucco Façade with Matching Road Construction, Glen Oaks, Queens, New York. 2019 © Rafael Herrin-Ferri

Spanish Pair 2, Laurelton, Queens, New York. 2019 © Rafael Herrin-Ferri

Speckled Two-Family Villa. College Point, Queens, New York. 2018 © Rafael Herrin-Ferri

Green Supreme. Jamaica, Queens, New York. 2019 © Rafael Herrin-Ferri

Two Musicians. Elmhurst, Queens, New York. 2018 © Rafael Herrin-Ferri

Big Blue Beyond. Forest Hills, Queens, New York. 2021 © Rafael Herrin-Ferri

⇣⇣⇣ Next Profile: Beregovich ⇣⇣⇣

Beregovich

Beregovich is a Brooklyn-based street photographer and oral historian.

Street photography continues to be a very popular genre of picture making, particularly for those who live in a city like New York where opportunities for making this kind of work are plentiful. The consequence of this popularity is an endless stream of street photos posted to social media platforms. In such a crowded space cliches are easy to spot, and a lot of the work starts to blend together. But in that often unvaried stream of images, some work still delivers. Beregovich is making that kind of work.

Maybe a person in one of Beregovich's photos is doing something mundane like waiting at a bus stop. Maybe, as they wait, a breeze blows their hair, and a memory runs through their mind of the way it felt when their mother would run her fingers through their hair.

That's the kind of moment I feel like Beregovich's best photos take us. We weren't there at the beginning, we won't be there at the end, we can't know what's really going on, but for a brief moment, we are in the middle of some stranger's life in all its strangeness and beauty and mystery.

I asked Beregovich to tell me a little about their life in photography:

“My last name is Beregovich and I don't know what my first name is yet. I think that's also representative of my photography, that I don't really know what to go by and I've noticed that a lot of my photos recently focus on an unknown individual. I'm a super privileged gay and non-binary person born in Manhattan and raised in Brooklyn my whole life and that's where I prefer to photograph nowadays.

“When I was 15, I got the iPhone 6 just in time for a vacation with my dad to Germany and Switzerland and took a ton of photos when we were there. I wasn't ever really interested in photography but the photos I took there of the lakes and mountains in the fog and small cities made me super excited to take more and that kind of excitement was new for me and I dug it big time. Soon after, I asked my parents if we had any cameras that I could use and they handed me a Nikon D60 that we've had for years. It came with 18-55mm and 55-200mm kit lenses and that thing went almost everywhere with me. That excitement kept growing and turned into a need. I got my first "serious" camera, the Nikon D750, in late 2017 and that excitement and need only got stronger.

“When I got the D750, I turned from cityscapes and portraits of my friends to street photography pretty quickly. There's really nothing like street photography. The rush is insane and it becomes close to an addiction. But I think what makes me so attracted to it is getting to see people you would never notice otherwise and places you've walked around a thousand times become completely new and I think that's pretty neat. I especially love photos that isolate one or two people. You get to learn a lot about social behavior and learn that, as predictable as some people and scenes can be, you can't really be prepared for any one scenario or encounter and have to be open to most everything. When you start to think that way, you never get bored again. And once you start thinking that everyone is just a person and no one is above or below you, more of the world opens up to you.